Just a quick reminder that I still blog over at Paths Through the Forests, the Patheos blog that I share with Rua Lupa. My newest post there, “The Pagan Ape“, went live this morning. In it I discuss our detachment from nature, the effects that detachment has, and what I feel our responsibility as pagans and humans may be to the planet. Read the post here!

Category Archives: Paganism

Totemism 201: Why Going Outside Matters

My apologies for the lack of posts as of late. February into March is generally a busy time for events in my vending and speaking schedule, and I’m just now entering a period where I’ll mostly be at home. I still have plenty of other things going on here in Portland, and the Tarot of Bones is still eating my life, but if all goes well there’ll be more blog posts. In my last post I said we were going to talk about a different topic. I’ve got one that’s really prominent in my head right now, though, so I’m going to cover it instead.

So in my travels over the last several weeks I’ve tried to get out into wilderness places at least a few times. I went hiking at Ed Levin County Park in San Jose while I was at PantheaCon, and on my way back home I stopped for a few hours to walk and drive around the Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge. Just this past weekend I did a bit of a birding hike at Minnehaha Falls Regional Park while in Minneapolis for Paganicon. All of these were excellent opportunities to appreciate species of wildlife I don’t normally get to see in Portland, and especially to appreciate the spring migration of dozens of species of bird.

I learned a lot in those excursions, but an experience at home helped to solidify some thoughts I’ve had about why this is so important to my totemic path. This morning I woke up just around dawn; my sleep schedule’s been a bit out of whack with all the travel through time zones and whatnot. So I headed into the living room to start checking email, and to enjoy the morning drama at the bird feeders on my porch. I have both suet and seed feeders, and it’s normal for me to get a variety of tiny feathered dinosaurs ranging from scrub jays to pine siskins to Northern flickers coming by for breakfast.

I’ve also recently discovered eBird, a joint effort by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the National Audubon Society. It’s a website that allows you to record your bird sightings, and I’ve been registering my feeder visitors as they show up. One of the entry fields asks for the sex of the bird, if you have that information handy. Some are pretty easy to discern–a male dark-eyed junco in Oregon looks very different from the female, being darker in color. Others, like scrub jays, have little to no sexual dimorphism. I’ve had a few Northern flickers by yesterday and this morning. On first glance the male and female look very much the same–brown with black barring on the back, and a black “bib” and spots on the chest, with either yellow or red shading on the the tail and wings. I wanted to be able to discern whether I had males or females–or both–showing up, so with a quick bit of Google research I found that the males tend to have a red or black spot on their cheeks.

Why is this important to totemism? Because the presence of both sexes indicates the strong possibility of nesting nearby, which means I can also keep an eye out at area trees for nesting holes and, if I’m lucky, young peeking their heads out as they get a bit older. Sure, I can also look up videos and articles about flicker family dynamics, but there’s something about getting to see it in person that I think would make my understanding of Flicker as a totem more full and vibrant.

See, the “meanings” of animal totems (here’s why I don’t like that concept, by the way) are largely drawn from the animals’ behavior and natural history. Scrub Jay was the first totem to greet me as soon as I moved to Portland almost right years ago, and its bold, brash curiosity was infectious as I began exploring my new urban home. Moving is always a stressful experience, even when it’s for positive reasons, and I’d spent a year in Seattle becoming progressively more depressed and unhappy. Rather than sinking deeper into that because I had to start all over in a new place yet again, I found myself drawn out into the world by a brilliant blue and gray bird.

And over the past eight years I’ve made more of a study of the natural history of this area, both Portland and beyond, from geology to climate to the various sorts of flora, fauna and fungi found in each place I’ve explored (and some I’ve yet to set foot in). I’ve deepened my connection to the land that’s embraced me, and I’ve created more substantial relationships with some of the totems here as well. I feel invested in this place and everyone who lives here, and I give more of myself than ever before.

Many totemists, especially newer ones, rely on totem dictionaries and feedback from on-topic internet forums and groups to get their information on what a totem “means” or whether an animal sighting was a message in disguise. While these can be useful at the beginning, eventually you have to drop the training wheels and figure things out for yourself. I’ve long said that what a particular totem tells me may not be what it tells you, and so coming to me and asking “What does Brown bear mean?” or “I saw a blue jay today, what does that mean” is useless. All I’ll tell you is to ask the totem itself, because that’s a relationship between the two of you.

And a big part of developing that relationship involves going outside–or, for those unable to do so, at least watching/listening/etc. from the window. Hell, barring all else there are books and documentaries and websites on all sorts of natural topics. Nature spirituality is meant to be about our connection with everything else, not just the human-dominated portions of the world, and if you only immerse yourself in dictionaries and forums you’re going to miss out on a lot. Going to wilder areas where we’re less of an influence serves to illustrate just how much we’ve affected the world around us, and what we stand to lose if we keep up our destructive ways. You can look at photos and video, but there’s nothing to compare with seeing it with your own eyes if you’re able to. A picture of a clearcut is devastating, but it’s nothing next to actually going out and walking through a devastated landscape where a forest has been torn down, being completely surrounded by shattered trunks and earth scraped bare.

It’s that sort of experience that helped me move from a “all about me” approach to totemism to a more balanced give and take. Totemism isn’t just about us, as I’ve talked about already, and in my next post I’ll be talking about why giving back through offerings and otherwise is crucial to one’s totemic practice.

A master list of Totemism 201 posts may be found here.

Did you enjoy this post? Please consider purchasing one or more of my books on totemism and related topics! They include more in-depth information on working with totems, to include topics not discussed in this essay series.

Announcing My Newest Project: The Tarot of Bones

Happy New Year, all! For the past several weeks I’ve been dropping hints here and there about a big, super-secret project I have in the works, and now I’m doing the big unveil:

After almost twenty years of practicing nature-based spirituality and creating art with natural materials, I am creating a tarot deck. The Tarot of Bones is an ambitious project combining the nature-inspired symbolism of animal bones with the tarot’s well-loved archetypes to create an unparalleled divination set for the 21st century. As animals exist within vibrant and complex ecosystems, the bones will be ensconced in permanent assemblage artworks using natural and reclaimed materials reflecting both the animal’s habitat and emblems of their respective cards.

The Tarot of Bones will be a complete 78-card tarot deck with both the Major and Minor Arcana, each card featuring a full-color photograph of the assemblage piece I create for it. A full companion book will also be available, detailing the symbolism and potential interpretations of each card, as well as sample layouts and other material of use to the reader. The Tarot of Bones will be self-published to allow me the greatest amount of creative control; I will be organizing a crowdfunding campaign later in 2015. If you would like to support my creative endeavors in the meantime and get access to exclusive work in progress photos of the artwork for the cards, please consider becoming my patron on Patreon.

For more information and updates please refer to the pages and other links at the official website; you may also wish to join our Facebook page (make sure you turn on notifications!) I’ll be posting pictures of the assemblage art for each of the 78 tarot cards in the deck-to-be. The first one will be up later in January; in the meantime, I invite you to take a peek at some of my other artwork on my portfolio; you can also see specific samples of my work on the main page of the Tarot of Bones website to give you some idea of the style I will be using for this deck.

And please share, reblog or otherwise pass this post on to anyone you feel may be interested; as I will not have the promotional power of a publisher behind me on this project, word of mouth is going to be a really important component of making it happen. Thank you!

Totemism 201: An Introduction and Purpose (And Master List of Totemism 201 Posts)

As of this upcoming spring it will be nineteen years since I became pagan and began working with totems, among other spiritual beings. While my path has wended its way through a variety of areas of study and practice, the totems have been a constant presence throughout. While my initial work was exclusively with animal totems, since moving to Portland in 2007 I’ve expanded my work to include the totems of plants, fungi, landforms, and other manifestations of nature. From the beginning my relationships with the totems have been influenced by my status as a non-indigenous person trying to bond with the land I found myself on. I’ve been inspired by others authors’ writings on the subject, both historical and contemporary, but rather than following traditions from other cultures I have primarily worked with the totems to create my own path.

Unlike a fair number of non-indigenous practitioners, I’ve taken these relationships far beyond the basic “This totem has this meaning” level. While I’m far from the only advanced neopagan totemist out there, I’d like to see more people move their practices past stereotyped meanings and begging totems for help. I recognize I’m somewhat in the minority in this regard. Most folks who pick up a book or hunt for a website on totemism are just looking for quick and easy answers like “What does the (totem) Fox say?” and “What sort of spiritual message am I getting when a highly territorial bird like a red-tailed hawk keeps showing up in my yard, using the nearby telephone pole as a perch to hunt for delicious, delicious rodents?” I prefer writing about more complex ways of relating to these spirit beings of nature, and insist that my readers do the work themselves, even if it takes years. While I have a growing audience of folks who agree, I’m not very likely to topple Ted Andrews and his eternally-loved Animal-Speak* for “most popular totemism book ever.”

So why do I feel it’s so important to grow one’s totemic practice when so many insist on buying into an easy-answers format? Well, for one thing there’s a lot more to learn from an individual totem than whatever blurb that’s passed around from one totem dictionary to the next. Just like any other relationship, your connection with a totem grows and evolves over time, and what they have to show you may expand far beyond what you read in such and such book; Gray Wolf may say nothing whatsoever about being a teacher, and Red-tailed Hawk may never mention being a messenger, and so forth. It’s crucial to cultivate an open mind; I’ve lost track of how many people I’ve seen posting in forums about how a totem tried to teach them something that wasn’t in the book, and rather than simply going with it they worried they were doing something wrong. I find that rather sad; when faced with such a situation I prefer to promote a sense of enthusiastic exploration over one of self-doubt.

More importantly, the common totemic paradigm is incredibly selfish. Look at almost any book or website on animal totems (or spirit animals, etc.) and the emphasis is on what you can get from these beings, how they resonate with you, how they can enhance your life, and so forth. As far as I’m concerned, one of the first steps to becoming a more advanced totemic practitioner is the realization that it’s not about you, and that you (and humanity in general) are only a very tiny portion of the grand scheme of things. Beyond that it’s imperative to look at what you can give back to the totems, their physical counterparts and the habitats they live in. The New Age emphasis on non-indigenous totemism keeps saying “take, take, take, take!”; my own practice has grown to encompass “give, give, give, give!” more and more as the years have passed by. The balance of give and take may shift over time; sometimes I need to rely more heavily on my totems than others. But I have long since given up the solely “What’s in it for me?” approach so popular with the dictionary style of totemism.

I’d like to see that trend spread. Each totem is the guardian of its own species; they’re concerned with far more than us, something we all too often ignore in our quest for personal enlightenment. We humans already take so much from the rest of the beings on this planet, and we insist on taking a lot from their totems without giving back to them. I want to foster an approach to totemism that nurtures a sense of responsibility toward the totems and their children rather than this “I want all the answers and I want them now!” approach that’s so popular.

When I wrote my first book, Fang and Fur, Blood and Bone, almost a decade ago, I wrote it because I was tired of totem dictionaries and wanted there to be more on totemism and animal magic than easy answers. My books and other writings have continued in that tradition, and you can consider this essay series the newest iteration thereof. You won’t find pre-scripted rituals here, and certainly not dictionary entries of what totems supposedly mean universally; I’m also not going to go into introductory material like how to find totems. It’s not an exhaustive how-to resource; that would be counter to its very intent. In part it’s a collection of essays punching holes in some (figurative) sacred cows of neopagan totemism. These writings are also meant to offer several potential starting points for expanding and growing your own practice in the directions you and your totems deem best. Let go of the idea that you have to grow your practice in a linear manner; instead, let it grow organically, and use the essays I write as seeds for that endeavor.

Master List of Totemism 201 Posts:

Totemism 201: Totems Are Not Pokémon

Totemism 201: Why Totem Dictionaries May Be Hazardous To Your Spiritual Growth

Totemism 201: Why Species Are Important

Totemism 201: It’s Not Just About the Animals

Totemism 201: It’s Not Just About Us, Either

Totemism 201: Why Going Outside is Important

Did you enjoy this post? Please consider purchasing one or more of my books on totemism and related topics! They include more in-depth information on working with totems, to include topics not discussed in this essay series.

* No offense to the late Mr. Andrews; his book was admittedly my first book on the topic, and while much of it is the sort of dictionary I don’t care for, he did include a lot of useful exercises for bonding more deeply with one’s totems, and my signed copy that I’ve been toting around for almost twenty years is one of my prized possessions on my bookshelf.

Art is Work

My friend and fellow creative person, Liv Rainey-Smith, shared a fantastic article by Sarah Manning over Facebook earlier this week. Entitled The Pomplamoose Problem: Artists Can’t Survive as Saints and Martyrs, it neatly skewers the idea that artists (and writers, and other creatives) shouldn’t seek financial recompense for our work, and that artists who place money as a priority are automatically sellouts. There’s a quote I particularly like:

It’s a dangerous, impossible standard that is repressing self-expression and killing culture…The American artist is expected to be both a saint and a martyr. Operate outside the capitalist system and we’ll praise you for your creations, call your poverty a quaint kind of martyrdom that has nothing to do with us, and at the same time resent you for being holier than thou. Try to operate within the capitalist system and we’ll call you out as an imposter.

With my own work, I find this attitude complicated further by the spiritual dimensions of my art and writing. Within the pagan, New Age and related communities, there’s a deep vein of mistrust of money and materialism, to the point where any sort of material comfort is seen as a dangerous seduction into evil. (There’s a great rebuttal by Jake Diebolt in this week’s guest post at my other blog, Paths Through the Forests.) Those seen as leaders (or who at least manage to publish at least one on-topic nonfiction book) are held to especial levels of scrutiny; spiritual enlightenment supposedly makes one immune to the needs of the physical world; achieve a certain amount of transcendence and you no longer need to pay rent, or so the theory seems to go.

Well, the only level of “transcendence” I know of in which a person no longer needs shelter is death, and I’m not there yet. Moreover, I intend to keep it that way as long as I can. And since I just got done talking about how we artists never seem to run out of ideas for projects, I think I can safely assume that most of my fellow creative types would like long lives full of opportunities to make neat things happen.

This means we need to have a place to live, food to eat, access to health care, and all the other things everyone else requires. And somehow this comes as a shock to certain people who appear to be under the misapprehension that, like a goldfish in a bowl, artists will happily subsist in the most minimal of living conditions simply for the joy of making art. What people often don’t realize about both goldfish and artists is that these minimal settings are inadequate. Goldfish are a type of carp which can grow quite large, and a plain bowl of water without regular filtration can quickly accumulate toxins, leading to either an unhealthy or dead goldfish. And while a human being can ostensibly live in an overcrowded slum apartment with bad food and alcohol taking the place of medical attention, over time such a lifestyle takes a serious physical and psychological toll.

This means we need to have a place to live, food to eat, access to health care, and all the other things everyone else requires. And somehow this comes as a shock to certain people who appear to be under the misapprehension that, like a goldfish in a bowl, artists will happily subsist in the most minimal of living conditions simply for the joy of making art. What people often don’t realize about both goldfish and artists is that these minimal settings are inadequate. Goldfish are a type of carp which can grow quite large, and a plain bowl of water without regular filtration can quickly accumulate toxins, leading to either an unhealthy or dead goldfish. And while a human being can ostensibly live in an overcrowded slum apartment with bad food and alcohol taking the place of medical attention, over time such a lifestyle takes a serious physical and psychological toll.

So it should come as no surprise when an artist finds a way to crawl out of that level of destitution, we take it. That’s when the real fun begins. We’ve ceased to be the romantic notion of the artist nobly starving for their art, putting the creative process and the spiritual efforts far above any material wants or needs. Instead we now demand the same realistic treatment as everyone else.

Most artists have day jobs; most of those who don’t have a spouse or other person taking care of their basic financial needs. That rarest of creatures, the creative person who subsists entirely on income from their work, is held up as the magical “someday goal” for those artists still chugging away as a barista or retail clerk or warehouse worker. “Maybe someday I’ll be a good/popular/prolific enough artist to get to that point!” they think. That dream carries them through the drudgery of what actually pays their bills. But it’s not all dreaming and scheming; when the toil of a job they hate becomes too much, they may lash out at their self-employed counterparts with a flail of envy. And that is part of what feeds into the “Artists shouldn’t make money from their art!” attitude. It’s spoiled dreams and sour grapes all the way.

Not every artist with a day job is so embittered. Some are quite content with what pays their bills; art has remained a hobby for them, a nice diversion at the end of the day to blow off some steam. They may give away everything they create to friends and family, buying more supplies with the surplus from their paychecks. Or they sell their wares for next to nothing, undercutting everyone else’s prices on Etsy or at the craft fair. There is no desperation there, no drive to draw a profit. Nothing wrong with that approach in and of itself. But it begs the question: why don’t more artists just go get day jobs in their field?

For many artists a steady gig, even if it is making art for someone else’s specs, is the ideal balance between paying the bills and expressing one’s creativity. Unfortunately, even freelance work is scarce, and the competition is vicious. Most of the jobs are for graphic artists, so anyone working in other media is likely to find slim pickings at best. And a full-time permanent position with benefits? You may as well toss a handful of chocolates into a throng of starving crows and watch the murder commence.

For many artists a steady gig, even if it is making art for someone else’s specs, is the ideal balance between paying the bills and expressing one’s creativity. Unfortunately, even freelance work is scarce, and the competition is vicious. Most of the jobs are for graphic artists, so anyone working in other media is likely to find slim pickings at best. And a full-time permanent position with benefits? You may as well toss a handful of chocolates into a throng of starving crows and watch the murder commence.

And yet, this is what’s held up to us as the solution to our problem. Go draw a steady paycheck like everyone else. Stop charging more than pocket change for your own work. Keep your art marginalized and low-paid so we can keep living down to that image of starvation and conformity. Be the shining example of uncorrupted creativity, untouched by filthy lucre.

Yes, what about that notion of corruption? Don’t sellout artists end up churning out crap because they’re more concerned with money than art? No more than anyone else. Everyone does what they need to to stay fed and sheltered; for some people that’s wrangling numbers in an accountant’s office, for others it’s detangling spaghetti code, and for still others it’s creating whatever commercial art an advertising studio wants. Sometimes artists do end up pandering to popular trends because that’s what pays the bills. it doesn’t mean they no longer put their creativity into the process, nor do they stop making more experimental art on their own time (and dime.)

Personally, I’ve found that an artist with the bills paid will make better art. When I have time to myself, when my commission list is empty and I don’t have any upcoming vending events, when I’ve made enough cash to cover rent and bills and other expenses, that’s when I really shine. Those are the golden moments when the stress of deadlines no longer holds me back, and I can make whatever the hell I want. I can try out new techniques; I can explore projects that may sit around unsold for years simply because they’re fun to make; I can try writing in a new genre I haven’t played with before. I couldn’t do these things if I wasn’t able to literally buy myself the breathing room to do so.

I want you to notice something very important: taking commissions and selling simpler, more popular pieces to pay the bills doesn’t take away my creativity. These “bread and butter” art sales are my equivalent to a day job; they enhance my ability to create the more experimental pieces I do on my own time. And unlike someone working a desk job, I am constantly using my artistic skills and keeping them honed; there’s no transition from work headspace to art headspace. It’s only a matter of what project I’m focused on at any given moment. I love every piece I create, too, from the simplest little pouch to the most elaborate headdress, and all points in between. But I also love having a roof over my head, and so I deliberately apportion time to different sorts of project so that I make sure I still have a place in which to work and materials to create with.

This is the reality of artists today: We are not your romantic notions, your symbols of the sylph-like elevated creative; our art is not automatically enhanced by hardship, nor should you enforce our hardship just to make us make art that you consider to be more “genuine.” We are people with real needs and problems, and we have to eat, too. We work every bit as hard as you do for each and every dollar, often for longer hours and less security.

And that’s the thing this culture needs to come to accept: art is work, and it’s okay to pay us for it, dammit.

Do you enjoy my writing and art? Want to make sure I can keep making cool stuff? Consider being my patron on Patreon, purchasing a piece of my art, or giving one of my books a home! And don’t forget to share this post on Facebook, Twitter, and elsewhere, too.

A Naturalist Pagan Approach to Gratitude

Supposedly Thanksgiving is about gratitude, a rather pagan-friendly appreciation of the harvest that will help us get through the hard winter ahead. In my experience, it’s primarily been a time to get together with family and/or friends, eat lots of food (and for some people get tipsy or drunk on whatever booze is available), and not have to go to work. Other than a prayer before the meal, I’ve observed very little overt gratitude being given amid the festivities. It’s not that I don’t appreciate the value of time with good people and plenty to eat, and I definitely disapprove of the growing trend of nonessential personnel having to work on Thanksgiving proper. But the original meaning of the holiday seems to have been rather lost in practice.

Perhaps this is in part because deliberate harvest festivals have been a part of my spirituality for the better part of two decades. Because I came to paganism after being raised Catholic, and I didn’t have a coven or other group to indoctrinate me formally with a predetermined set of spiritual parameters, I had to really consider what beliefs and practices I was adhering to and why. So I learned about the three harvest Sabbats–Lammas, Fall Equinox, and Samhain–and their historical counterparts in various European cultures. As I spent more time gardening, I was able to put theoretical practices to the test, exercising a new layer of gratitude as I watched seeds I planted sprout, grow, and come to fruition. The older I got and the more my path developed, the less I took my spirituality for granted.

These days, gratitude is deeply ingrained in my path because I know too much now to sustain ignorance. My roots are firmly embedded in urban sustainability and environmental awareness, and so I am acutely aware of where my food comes from and the cost it exacts on the land. “Harvest” isn’t just something to be celebrated in autumn; I’m able to get all sorts of food year-round, and that means there’s a harvest going on somewhere every day. As much as I try to stay local and seasonal, it’s not always within my budget (financial or temporal), and so I sometimes find myself buying out of season produce flown in from far away and processed foods whose ingredients were harvested weeks ago, moreso in the winter.

This means that each meal is infused with awareness and appreciation for the origins of each of the ingredients, whether I grew them myself or not. I can’t help but be grateful to those who made sure I was able to eat, whether that’s the animals, plants and fungi that died (or were at least trimmed back) to feed me, or the people who took care of them throughout their lives, or those who harvested and prepared them. I also have gratitude for the land that supported the food as it grew, particularly those places where chemical pesticides, fertilizers and other “enhancements” have destroyed the health of the soil. And I think, too, of the air, water, and land polluted by the fossil fuels used to grow, process and transport the food to me, and the other wastes that result from the sometimes convoluted path from farm to table.

All of this is summed up in a short prayer I’ve said before meals–quietly or out loud–for many years:

Thank you to all those who have given of themselves to feed me, whether directly or indirectly.

May I learn to be as generous as you.

Notice there’s two parts to that prayer–the acknowledgement of what others have given to me, and a hope that I can be as giving myself. Considering how much some beings sacrifice in order for me to eat, it’s impossible for me to give back exactly as much, at least until I die and my body is buried in the ground to be recycled into nutrients for others. But I can try to give back through more sustainable food choices, and attending to the tiny patch of land in my community garden, and donating food to charity. I can support efforts to gain better rights and working conditions for the migrant workers who pick the produce I eat and the underpaid employees of food processing plants. I can work to educate others about the problems inherent in our food systems and what we can do about them. All these are a far cry from being as generous as a being that died to feed me, but they’re a start.

My gratitude drives me to do what I can each day, not only to appreciate what I’m given but to care for those who have given it to me. The more I know about where my food comes from, the more driven I am to be a responsible part of this unimaginably large network of supply and demand, resource and consumption. Being grateful isn’t just about taking things with a “Yes, thank you”. It’s also the desire to give back, to demonstrate appreciation. The prayer at the beginning of the meal is only the barest glimmer of that urge, and it means little if it’s not followed up by action.

And so this Thanksgiving, as I am surrounded by others and as we prepare to eat turkey and stuffing and green beans and the canned cranberry sauce that retains its cylindrical shape all by itself, it’ll just be another day in which I am grateful and in which I try to enact as well as voice that gratitude. It’s also a good day to renew my commitment to that thankfulness and all it entails, in thought and deed alike. I may never achieve perfection; there are always more thanks to be given. But let this time of year be the rejuvenation of my efforts nonetheless.

A Potpourri of News and Stuff

I’ve been funneling most of my writing time over the past week toward a new book manuscript that, for now, shall remain under wraps. In the meantime, here’s what else I’ve been up to:

–Along with vending and leading a workshop on repurposing leather clothing in crafts, I entered a few pieces of my art in the art show at OryCon 36. I was absolutely thrilled when I found out The Teacup Tauntaun won the Popular Choice award, complete with shiny blue ribbon! What does that mean? Well, apparently a LOT of people liked my attempt to turn an old Corsican ram taxidermy mount into the wild beast of Hoth, and while she didn’t find a new home with someone else, she did bring home some bragging rights.

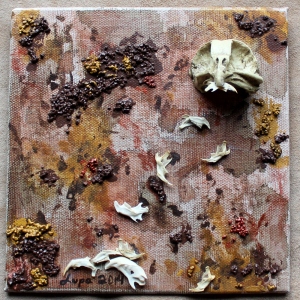

–Speaking of art shows, you can see (and purchase) another one of my assemblage pieces, “Raptor’s Feast”, at the Wild Arts Festival held by the Audubon Society of Portland on November 22-23, 2014. I created it to donate to the 6×6 Wild Art Project, where artists create pieces measuring no more than 6″ x 6″ x 2.5″; these are then sold at the Wild Arts Festival and 100% of the proceeds benefits the Audubon Society of Portland and their efforts to protect local birds and their habitats. “Raptor’s Feast” is a 6″ x 6″ canvas board painted in acrylics, with used grit from my rock tumbler added for texture, a resin hawk skull, and real rodent jaws from owl pellets.

–Speaking of art shows, you can see (and purchase) another one of my assemblage pieces, “Raptor’s Feast”, at the Wild Arts Festival held by the Audubon Society of Portland on November 22-23, 2014. I created it to donate to the 6×6 Wild Art Project, where artists create pieces measuring no more than 6″ x 6″ x 2.5″; these are then sold at the Wild Arts Festival and 100% of the proceeds benefits the Audubon Society of Portland and their efforts to protect local birds and their habitats. “Raptor’s Feast” is a 6″ x 6″ canvas board painted in acrylics, with used grit from my rock tumbler added for texture, a resin hawk skull, and real rodent jaws from owl pellets.

–I’m pleased to announce that I am a Guest of Honor at Paganicon 2015. Held in the Twin Cities in Minnesota, this is the 5th year for this well-received pagan convention. I’ll be signing books, leading workshops, and enjoying being back in the area for the first time in a decade. Head to the official website for more information.

—I’m also going to be presenting at PantheaCon 2015 in February; my workshop, “Animal Skulls as Ritual Partners”, scheduled for 9am on Sunday, February 15, 2015 will involve some introductory information on working with animal skulls in spiritual practices, along with some hands-on experience. So bring your favorite skull (or borrow one of the ones I’ll have with me) and be prepared for what is often considered a very moving spiritual experience! (I’ll have some other events happening, both at the convention off-site–more info on that later.)

–Finally, I’m working hard on Curious Gallery, my two-day arts festival celebrating cabinets of curiosity and their contents. Its next iteration will be January 10-11, 2015 at the Crowne Plaza Portland-Downtown Convention Center here in Portland, OR. We’ve already got some great programming arranged with more in the works, and we’re still accepting programming and vending applications, with art applications opening soon. The early bird weekend rates end after November 16, so register now!

–Finally, I’m working hard on Curious Gallery, my two-day arts festival celebrating cabinets of curiosity and their contents. Its next iteration will be January 10-11, 2015 at the Crowne Plaza Portland-Downtown Convention Center here in Portland, OR. We’ve already got some great programming arranged with more in the works, and we’re still accepting programming and vending applications, with art applications opening soon. The early bird weekend rates end after November 16, so register now!

So, Lupa, How *Do* We Make Nature Spirituality More About Nature?

Note: I fiddled around with settings on my site; you can now email-subscribe to my blog from any post, rather than on the front page of the blog itself. It’s a great way to keep up on my writing, news, and more–just plug your preferred email address into the box on the right sidebar of this (or any other) post!

In my previous post I made the assertion that a lot of what’s considered to be “nature-based spirituality” is really more about us than the rest of nature. Here I’d like to present some further food for thought, and invite other naturalist pagans and the like to reflect on where the balance between human and non-human nature may be in your own paths.

I’m going to add in my own thoughts on each of these questions, but please don’t take my responses as holy writ; I mainly offer them up in the spirit of “here, I’ll go first, since I proposed this whole thing to begin with”.

—Why should we be concerned about the balance of human and non-human nature in nature spirituality?

Humanity, as a whole, is really, really self-centered. This isn’t surprising; favoring one’s own species has been a successful strategy for us and many other species for millions of years. However, one of the things we humans have evolved to face the challenges of everyday life is a big, complex, self-aware brain. This allows us to be more deliberately conscious of our choices and motivations, and to change them if we will. For example, we still have the genetic programming to gather as many food resources together as we can to feel secure; however, we also consciously recognize the devastating impact that our food consumption has on the rest of nature, and the unequal distribution of food within our own species. Therefore, we’re able to (ideally) adjust our behaviors to still get the food we need, but be less destructive in the process.

In the same vein, spirituality is one way we can make sense of the world around us and our place in it. But a lot of “nature” spirituality is really more about us than about the rest of nature. It’s about what special messages and teachings and other gifts we can get from the animals, plants and other beings around us, without having to give anything back. We might show some gratitude for things like a healthy harvest, but that’s still focusing on how nature benefits us. It’s more like “humans asking and thanking nature for stuff” spirituality. We keep inserting ourselves into the middle of things.

—How does the emphasis on things like totem dictionaries, animal omens, and other “instant gratification” in nature spirituality mirror our consumption of physical resources?

Look at the shelves in pagan book stores, or the offerings from pagan publishers. They’re full of books on “the powers and meanings of animal totems” and “how to use herbs and crystals in spells” and other “get your answers right here, right now!” approaches. There’s not a lot on taking the time to create deeper, more personally meaningful relationships with other beings in nature, and even less on what we can do for our fellow beings (other than misguided advice to feed wildlife food offerings, and vague, generic “let’s send healing energy to the Earth” rituals, and so forth).

This is a direct corollary to our consumption of physical resources from nature, whether food or shelter or other tangibles. The vast majority of people, at least in the U.S., only care about nature as far as they can benefit from it. And they want their stuff now. They want to go to the store and get everything on their shopping list, whether that’s breakfast cereal and soda, or a new outfit, or cheap metal jewelry that will leave a green mark on the wearer’s skin but which makes an inexpensive gift for that relative you never know what to get for Christmas. Most people who go to national parks never venture more than a hundred yards from their cars; they oooh and ahhh at the highlights and maybe take some photos, but fewer make the connection between the preservation of these places and their own environmentally destructive actions at home.

And that’s the crux of the issue: fast-food nature spirituality continues this disconnect between our beliefs and our actions. We say we want to revere nature, but our actual interactions are brief and on the surface. Most of the people who claim Gray Wolf is their totem have never given money to an organization that works to protect wolves and the habitats they rely on to survive (though they may have bought t-shirts, statues, and other mass-produced, environmentally-unfriendly tchotchkes with wolves on them). We want something that will make us feel good and “more spiritual” in the moment, but it’s tougher to get us to engage with the deeper implications of finding the sacred in a nature that we too often damage in our reverence. The demand for totem dictionaries and other easy answers just perpetuates this trend.

—How does the human-centric focus of some elements of nature spirituality reflect the human-centric focus of more mainstream religions?

Most religions start with us. Sometimes we are the chosen creation of some deity; other times one of our own achieves divine status. There might be some directive to “be nice to animals”, or in some cases refrain from eating some or all of them. But for the most part, the bigger religions are about us and our relationship to the divine, what we humans are supposed to do to earn a good afterlife, etc.

Most pagans were raised in such religions, which reflect the anthropocentrism of most existing human cultures. So it’s not surprising that when we move over to paganism for whatever reasons, we take this human-centric view with us. How do we please the gods? What sorts of nifty things can we get with spells and other magic? And, of course, what special messages does nature have for us human beings?

I, among many (though not all) other pagans, became pagan because the idea of a spiritual path that focused on nature was appealing to me, almost twenty years ago now. I didn’t realize it then, but what I was searching for wasn’t rituals and rules on how to be a good pagan; what I really wanted was to reconnect with nature, without intermediaries and without abstractions, the way I did when I was young and before life got complicated. And now that I’ve managed to rekindle that, I’m realizing just how much of purported nature-based spirituality in general really isn’t based in nature at all, except for human nature. And it just perpetuates the same human-centric patterns I was trying to move away from when I became pagan in the first place. Not all pagans are naturalist pagans, so for some a more human-based approach works. But those of us who do claim nature as the center of what is sacred may not be looking deeply enough into nature outside of ourselves.

—How can we start shifting our focus away from ourselves and more toward the rest of nature?

Naturalist paganism and other forms of nature spirituality have the potential to break us out of that anthropocentric headspace, to remind us that we, the ape Homo sapiens sapiens, are just one species among thousands. For that to happen, we need to be paying more attention to the other species and parts of nature, and not just in manners that earn us freebies from the Universe.

We can start by becoming more aware of how often we ask the question “What do I get out of this?”, whether we use those words or not. This leads to an awareness of how much of our relationships to the rest of nature hinge on what we get from the deal. Sometimes it’s in the obvious places like assuming every animal sighting is a super-special message from nature, or focusing seasonal rituals only on the harvest of foods we’re able to eat and ignoring everything else happening in nature right then. But this self-centered approach can be more subtle, like using herbs in a spell but never once acknowledging the sacrifice the plants made and the resources they’d need to replace the leaves and other parts taken from them (assuming they weren’t just killed outright for their roots). By being aware of where we’re holding our hands out for gimmes, we can stop taking nature for granted so much.

Next, we can start incorporating the question “What can I give?” into our nature spirituality, again not necessarily using those words. What offerings do we make and to whom, and what actual benefit will they have to physical nature versus the harm? Part of why I emphasize donations and volunteering toward environmental causes as offerings is because they have an actual, measurable positive impact, much more than “I’m going to send some energy to endangered species by burning this petroleum-based candle made with toxic dyes”. If we take leaves from a plant for a spell, what do we give the plant in return? Is it something it can actually use, like water on a hot day, or something absolutely useless like sprinkling a few chips of quartz on the ground around its stem? Can we redirect our resources in more beneficial ways, like instead of buying a cheap wolf statue made in China we use the money (even a few dollars) to help fund the restoration of gray wolf habitat?

We can also start putting more emphasis on appreciating and honoring nature in its own right. A great way to do this is by simply learning more about biology, geology, and other natural sciences, and being able to appreciate the beings and forces of nature without having some spiritual or symbolic overlay involved. The fox that darts out into our path ceases to immediately be a portent of some important spiritual message, and instead becomes a remarkable creature borne out of billions of years of evolution and natural selection, whose strategies for surviving and adapting are equally effective as our own. And that’s all that creature has to be–amazing for itself regardless of some subjective “meaning” we glue to it.

Finally, we can realistically assess how much we’re walking our talk. I remember the very first big, public pagan gathering I went to; it was a picnic in a park, and all the food was on styrofoam plates with plastic utensils that all ended up in a big garbage bag destined for the landfill at the end of the day. It was incredibly disheartening since many of these pagans claimed to be nature-based in their own practices, and the ritual they performed even gave lip service to the “sacredness of nature”. Now, I understand that they probably didn’t want to wash a bunch of glass and ceramic dishes at the end of the day, and maybe didn’t want to spend the extra money for paper plates made from recycled paper, and perhaps they didn’t think to ask everyone to bring their own dishes to the event.

But this dissonance was important, because it gave me reason to assess my own actions and why I took them. It was the first in a long line of events that made me think “Wow, I want to do things differently”. Not “I’m a better pagan than they are”, but a realization that this thing bothered me and I wanted to make a different choice. And perhaps for those pagans, simply gathering outside on a sunny day was nature enough for them. But I wanted more, and I think naturalist paganism in particular would do well to include encouragement toward regularly assessing and improving one’s actions in relation to one’s beliefs when it comes to nature and the environment.

Here’s where a lot of people run into the sticky trap of dogma. I’m betting a lot of readers have, like me, run into that one variant of Wiccan who interprets “An if harm none” to mean “don’t eat animals!” and then insists that only vegetarians can truly be Wiccan. That’s just one example of where personal choice turns into an attempt to sic one’s dogma onto others. I don’t want to advocate that here. Just as each person’s spiritual path varies according to their needs and restrictions, so too are the actions associated with that path dictated by individual limitations and choices.

More importantly, it’s awareness, reflection, and conscious choice that are at play here. I am well aware that the car I drive, even if it does get pretty good mileage, still contributes to climate change and other results of pollution. However, I would not be able to vend my artwork at events, or take huge piles of packages to the post office, or run weekly errands associated with my business, if I didn’t have my car. Or at least it would eat a lot more into my time and lower my income more than what I currently pay for its maintenance and upkeep. But I try to balance that out by keeping it in good working order and not driving it more than I need to, and by walking or taking transit when I can. It’s that consideration and carefully-made choice that is more important than blindly adhering to the idea that if you have a car you don’t love nature enough.

And that brings me to the last question to ponder: What can I realistically change in my life right now to be more in line with my approach to nature spirituality? This is a question we can ask repeatedly–even every day, if that’s appropriate. The answer is likely to change quite a bit over time through growth and knowledge and experience. But that’s part of having a living, evolving spiritual path: you have to give it space to grow. The answers aren’t all set up in one concise book somewhere. They’re organic and they adapt to change much as we do. It’s a challenge sometimes to always be updating one’s path, to incorporate new information and reflections, and occasionally it may be tempting to just find a one-stop-shop for all the secrets of the universe.

But nature isn’t stagnant, and we only fool ourselves into thinking that only religion stands solid. If we are going to truly align ourselves with the currents and courses of the natural world, if we’re going to understand even a bit of what nature really is, then like the rest of nature we need to be prepared to adapt and explore. That means putting down the book of easy answers and “meanings”, and opening our senses to the world around us.

Sure, it’s scary sometimes, but exciting and full of curiosity, too. And I’m right here with you; you’re always welcome to comment or email me with your questions or thoughts as you walk your own path.

Eco-Friendly Pagan Ritual Tools–On the Cheap

It’s Earth Day, and while my blog tends to be pretty eco-centric year-round, I wanted to write today about a particular topic that comes up a lot in paganism, particularly among newcomers: ritual tools. Now, it’s been said many times by many people that you don’t actually need tools to be a pagan. I do agree that you can perform rituals open-handed, with nothing but yourself and the spirits/gods/energy you’re working with to make things happen. However, some people just like having the tools themselves; they help heighten the ability to suspend disbelief. And some people feel their tools have spirits of their own, thus making them allies in ritual.

–The wax is probably petroleum-based, which means it benefits from fossil fuel subsidies from federal and state governments. The chemical company that developed the dye might also have gotten subsidies as well. This means that these companies are getting money for free, out of people’s taxes, and therefore can sell their products more cheaply. These companies are also usually not required to pay for the effects of the pollution that’s a byproduct of their processes.

–The candles were likely to have been made by underpaid, sometimes abused workers in a factory in China or another East Asian country, with inadequate protection against the chemicals and machinery being used. There’s a good chance that any chemical byproducts of the process are not properly disposed of, and may just be dumped directly into the nearest river, saving them the cost of paying for safer options.

–They were shipped en masse on a boat from their country of manufacture to wherever you are, again using subsidized fossil fuels. The shipping company doesn’t have to pay for the pollution their boats cause to the ocean and the air, so they can keep their costs down.

We don’t have a solid number on the real cost of pollution from the manufacture of these candles, but suffice it to say you’re getting your candles cheaply in part because the entities who made them and their components are passing some of the cost on to the environment. And we add to that, too, any time we burn candles made with noxious chemicals that add to air pollution in our homes and elsewhere. We speak with our dollars when we buy these cheap things–we say “We don’t care, so long as we save a few bucks in the name of practicing a nature religion*”.

So what’s a pagan to do when money’s thin on the ground? Here are some options.

Use What You’ve Got

These are just a few ideas based on one particular set of ritual tools; you can get pretty creative depending on your needs, so treat it like a grand scavenger hunt! (Just make sure that you’re using only your stuff, or that you ask permission to use anything that belongs to someone else.)

Secondhand First

I am a huge fan of thrift stores and other secondhand shops. Sadly, here in the U.S. there’s a lot of consumerism, with much more stuff being produced for our demands than is absolutely necessary. I wrote a few years ago about the immense amount of clothing, housewares and other discarded stuff I found at just one Goodwill outlet store in just one city, and wondered how much more goes to waste every day. A lot of it is perfectly serviceable, too. I could easily build a dozen altars with the items found in one thrift store.

Yet there’s this unfortunate superstition floating around paganism that somehow you can’t cleanse secondhand items, that the histories they have will linger with them and will always taint them as ritual items–but of course, all a brand-new item needs is a quick cleansing! I call bollocks on that one. If you can purify a new glass bowl that’s been made in a sweatshop soaked in human suffering and death, created from materials that cause great devastation to the natural environment, and conveyed to your town while leaving a trail of fossil fuel pollution behind it, you can damned well purify the energy of a similar, secondhand glass bowl that sat on someone’s grandmother’s dining room table with wax fruit in it for thirty years. Most of my ritual tools over the years were secondhand, to include items that other practitioners used in their own rites, and I never had a problem making them ready for my work.

So get over that superstition, and start thrifting! You never know what kind of cool stuff you may find. (My only caution is that it’s really easy to come home with a cart full of secondhand tchotchkes for cheap, which may put shelf space in your home at a premium.)

Foraging At Its Finest

Many nature pagans like having sticks, stones and other natural items in their homes to remind them of what they feel is sacred. In fact, you can make your entire array of ritual tools from things you found outside. If you work with the four cardinal directions and elements, for example, you might have a stone in the north, a feather or bit of dandelion fluff in the east, dried wood or moss as firestarter in the south, and a vial of rain water in the west. The best part of all this is that, other than some containers for things like water, it’s all free.

Many nature pagans like having sticks, stones and other natural items in their homes to remind them of what they feel is sacred. In fact, you can make your entire array of ritual tools from things you found outside. If you work with the four cardinal directions and elements, for example, you might have a stone in the north, a feather or bit of dandelion fluff in the east, dried wood or moss as firestarter in the south, and a vial of rain water in the west. The best part of all this is that, other than some containers for things like water, it’s all free.

Do keep in mind there are certain legal and other restrictions. Federal and state parks in the U.S., for example, prohibit the collection of any natural items found within the park without a permit (some cities do this as well). You’ll need to ask permission when foraging on private property. And some items, such as some animal parts, are illegal to possess regardless of how you got them; most wild bird feathers in the U.S. cannot be possessed, even if they were naturally molted, as one example. (You can access my database of animal parts laws here.)

Grow or Make Your Own

DIY is a wonderful thing. Not only do you get to cut costs, but you get to gain skills, too! For example, some folks like to use herbs in their spells and other magic, and luckily a lot of these herbs can be easily grown, even in a pot by the window. If you worry about having a black thumb, there’s plenty of information on the internet about how best to care for a particular kind of plant; the most common ways to kill your herbs is through too much or too little water and sunlight, the wrong sort of soil or not enough fertilizer, and disease or parasites. If you notice a plant isn’t thriving, you can research online or in books at the library what the possible causes may be, and you can ask garden shops or people on gardening forums for advice.

Other tools can be homemade, too. If you want to have a permanently decorated altar, maybe with a scene depicting your patron deities or symbols of the four cardinal directions, you can paint a secondhand table with acrylic paints**, or carve or burn the designs if the table’s wood. A well-worn broom can be decorated with dried flowers and ribbon, and even re-bristled with straw and other plant materials. A particularly sturdy branch may make a nice wand as-is, or you can choose to decorate it to your preferences.

Support Local Artisans

You’re always welcome to ask an artisan about their materials. I talked earlier about cheap, petroleum-based candles from the dollar store; however, there are candle-makers who specialize in eco-friendly alternatives like beeswax and natural dyes, and who avoid candle wicking with lead in it. And the same goes for everything from ceramics to woodworking to paintings; usually there’s somebody who specializes in greener materials out there.

(Shameless plug for my own recycled hide and bone and other natural materials art here, though there are many artisans within the pagan community and elsewhere whose works would be lovely ritual items. Try Etsy, Artfire, and Storenvy for some possibilities.)

Conclusion

I hope now that you see that buying ritual tools on a budget doesn’t have to feed into environmentally harmful processes and practices. In fact, taking care in one’s shopping choices can be an act of spiritual devotion in and of itself. If you feel nature is sacred, then let that speak not just through your rituals and special moments, but in your everyday actions as well.

* With the understanding, of course, that not every person who identifies as a pagan focuses their paganism on nature, and there are some pagans for whom the gods, for example, are central.

** While not without their pollutants, acrylic paints are some of the safest paints that are easily obtained commercially. There are more eco-friendly recipes for homemade paints out there, but acrylics are best if you don’t want to go quite that far in your DIY-dom.

*** The effectiveness of a tool, by the way, is not in how pretty it is or how perfectly crafted. Even if you don’t think you’re an artist, it’s the intent behind the creation that matters. So don’t let that get in the way of making your own tools if you’re so inclined.