Note: I fiddled around with settings on my site; you can now email-subscribe to my blog from any post, rather than on the front page of the blog itself. It’s a great way to keep up on my writing, news, and more–just plug your preferred email address into the box on the right sidebar of this (or any other) post!

In my previous post I made the assertion that a lot of what’s considered to be “nature-based spirituality” is really more about us than the rest of nature. Here I’d like to present some further food for thought, and invite other naturalist pagans and the like to reflect on where the balance between human and non-human nature may be in your own paths.

I’m going to add in my own thoughts on each of these questions, but please don’t take my responses as holy writ; I mainly offer them up in the spirit of “here, I’ll go first, since I proposed this whole thing to begin with”.

—Why should we be concerned about the balance of human and non-human nature in nature spirituality?

Humanity, as a whole, is really, really self-centered. This isn’t surprising; favoring one’s own species has been a successful strategy for us and many other species for millions of years. However, one of the things we humans have evolved to face the challenges of everyday life is a big, complex, self-aware brain. This allows us to be more deliberately conscious of our choices and motivations, and to change them if we will. For example, we still have the genetic programming to gather as many food resources together as we can to feel secure; however, we also consciously recognize the devastating impact that our food consumption has on the rest of nature, and the unequal distribution of food within our own species. Therefore, we’re able to (ideally) adjust our behaviors to still get the food we need, but be less destructive in the process.

In the same vein, spirituality is one way we can make sense of the world around us and our place in it. But a lot of “nature” spirituality is really more about us than about the rest of nature. It’s about what special messages and teachings and other gifts we can get from the animals, plants and other beings around us, without having to give anything back. We might show some gratitude for things like a healthy harvest, but that’s still focusing on how nature benefits us. It’s more like “humans asking and thanking nature for stuff” spirituality. We keep inserting ourselves into the middle of things.

—How does the emphasis on things like totem dictionaries, animal omens, and other “instant gratification” in nature spirituality mirror our consumption of physical resources?

Look at the shelves in pagan book stores, or the offerings from pagan publishers. They’re full of books on “the powers and meanings of animal totems” and “how to use herbs and crystals in spells” and other “get your answers right here, right now!” approaches. There’s not a lot on taking the time to create deeper, more personally meaningful relationships with other beings in nature, and even less on what we can do for our fellow beings (other than misguided advice to feed wildlife food offerings, and vague, generic “let’s send healing energy to the Earth” rituals, and so forth).

This is a direct corollary to our consumption of physical resources from nature, whether food or shelter or other tangibles. The vast majority of people, at least in the U.S., only care about nature as far as they can benefit from it. And they want their stuff now. They want to go to the store and get everything on their shopping list, whether that’s breakfast cereal and soda, or a new outfit, or cheap metal jewelry that will leave a green mark on the wearer’s skin but which makes an inexpensive gift for that relative you never know what to get for Christmas. Most people who go to national parks never venture more than a hundred yards from their cars; they oooh and ahhh at the highlights and maybe take some photos, but fewer make the connection between the preservation of these places and their own environmentally destructive actions at home.

And that’s the crux of the issue: fast-food nature spirituality continues this disconnect between our beliefs and our actions. We say we want to revere nature, but our actual interactions are brief and on the surface. Most of the people who claim Gray Wolf is their totem have never given money to an organization that works to protect wolves and the habitats they rely on to survive (though they may have bought t-shirts, statues, and other mass-produced, environmentally-unfriendly tchotchkes with wolves on them). We want something that will make us feel good and “more spiritual” in the moment, but it’s tougher to get us to engage with the deeper implications of finding the sacred in a nature that we too often damage in our reverence. The demand for totem dictionaries and other easy answers just perpetuates this trend.

—How does the human-centric focus of some elements of nature spirituality reflect the human-centric focus of more mainstream religions?

Most religions start with us. Sometimes we are the chosen creation of some deity; other times one of our own achieves divine status. There might be some directive to “be nice to animals”, or in some cases refrain from eating some or all of them. But for the most part, the bigger religions are about us and our relationship to the divine, what we humans are supposed to do to earn a good afterlife, etc.

Most pagans were raised in such religions, which reflect the anthropocentrism of most existing human cultures. So it’s not surprising that when we move over to paganism for whatever reasons, we take this human-centric view with us. How do we please the gods? What sorts of nifty things can we get with spells and other magic? And, of course, what special messages does nature have for us human beings?

I, among many (though not all) other pagans, became pagan because the idea of a spiritual path that focused on nature was appealing to me, almost twenty years ago now. I didn’t realize it then, but what I was searching for wasn’t rituals and rules on how to be a good pagan; what I really wanted was to reconnect with nature, without intermediaries and without abstractions, the way I did when I was young and before life got complicated. And now that I’ve managed to rekindle that, I’m realizing just how much of purported nature-based spirituality in general really isn’t based in nature at all, except for human nature. And it just perpetuates the same human-centric patterns I was trying to move away from when I became pagan in the first place. Not all pagans are naturalist pagans, so for some a more human-based approach works. But those of us who do claim nature as the center of what is sacred may not be looking deeply enough into nature outside of ourselves.

—How can we start shifting our focus away from ourselves and more toward the rest of nature?

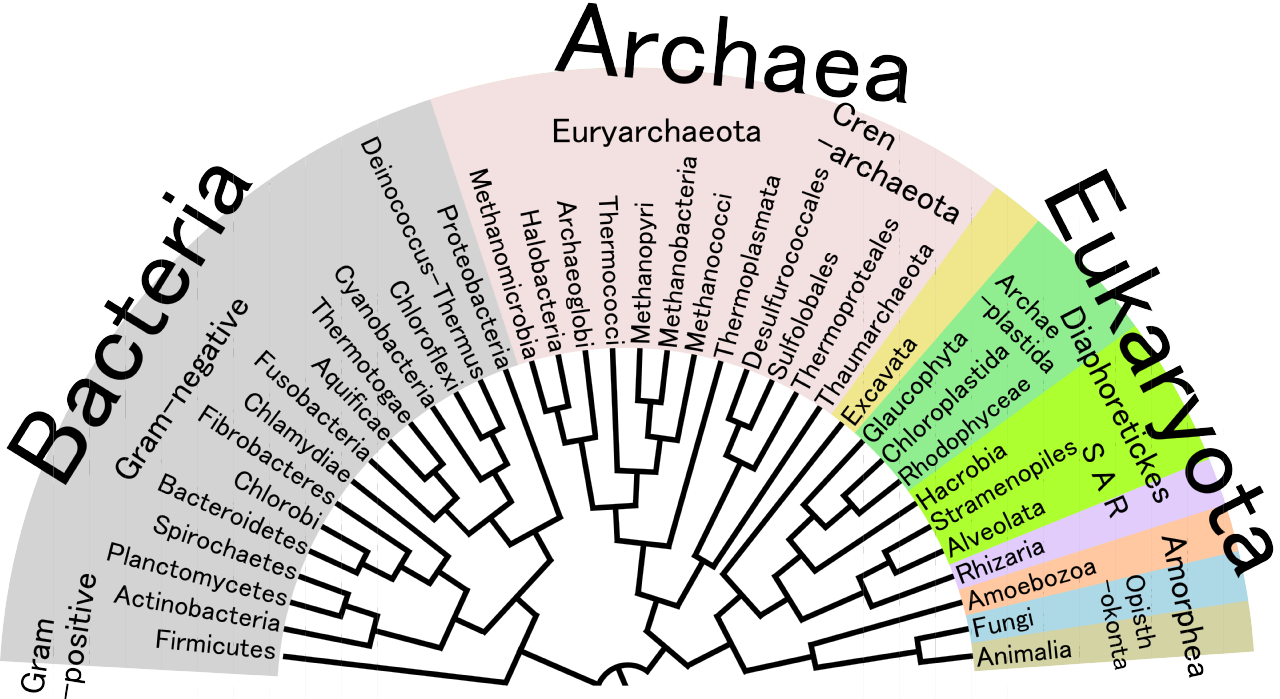

Naturalist paganism and other forms of nature spirituality have the potential to break us out of that anthropocentric headspace, to remind us that we, the ape Homo sapiens sapiens, are just one species among thousands. For that to happen, we need to be paying more attention to the other species and parts of nature, and not just in manners that earn us freebies from the Universe.

We can start by becoming more aware of how often we ask the question “What do I get out of this?”, whether we use those words or not. This leads to an awareness of how much of our relationships to the rest of nature hinge on what we get from the deal. Sometimes it’s in the obvious places like assuming every animal sighting is a super-special message from nature, or focusing seasonal rituals only on the harvest of foods we’re able to eat and ignoring everything else happening in nature right then. But this self-centered approach can be more subtle, like using herbs in a spell but never once acknowledging the sacrifice the plants made and the resources they’d need to replace the leaves and other parts taken from them (assuming they weren’t just killed outright for their roots). By being aware of where we’re holding our hands out for gimmes, we can stop taking nature for granted so much.

Next, we can start incorporating the question “What can I give?” into our nature spirituality, again not necessarily using those words. What offerings do we make and to whom, and what actual benefit will they have to physical nature versus the harm? Part of why I emphasize donations and volunteering toward environmental causes as offerings is because they have an actual, measurable positive impact, much more than “I’m going to send some energy to endangered species by burning this petroleum-based candle made with toxic dyes”. If we take leaves from a plant for a spell, what do we give the plant in return? Is it something it can actually use, like water on a hot day, or something absolutely useless like sprinkling a few chips of quartz on the ground around its stem? Can we redirect our resources in more beneficial ways, like instead of buying a cheap wolf statue made in China we use the money (even a few dollars) to help fund the restoration of gray wolf habitat?

We can also start putting more emphasis on appreciating and honoring nature in its own right. A great way to do this is by simply learning more about biology, geology, and other natural sciences, and being able to appreciate the beings and forces of nature without having some spiritual or symbolic overlay involved. The fox that darts out into our path ceases to immediately be a portent of some important spiritual message, and instead becomes a remarkable creature borne out of billions of years of evolution and natural selection, whose strategies for surviving and adapting are equally effective as our own. And that’s all that creature has to be–amazing for itself regardless of some subjective “meaning” we glue to it.

Finally, we can realistically assess how much we’re walking our talk. I remember the very first big, public pagan gathering I went to; it was a picnic in a park, and all the food was on styrofoam plates with plastic utensils that all ended up in a big garbage bag destined for the landfill at the end of the day. It was incredibly disheartening since many of these pagans claimed to be nature-based in their own practices, and the ritual they performed even gave lip service to the “sacredness of nature”. Now, I understand that they probably didn’t want to wash a bunch of glass and ceramic dishes at the end of the day, and maybe didn’t want to spend the extra money for paper plates made from recycled paper, and perhaps they didn’t think to ask everyone to bring their own dishes to the event.

But this dissonance was important, because it gave me reason to assess my own actions and why I took them. It was the first in a long line of events that made me think “Wow, I want to do things differently”. Not “I’m a better pagan than they are”, but a realization that this thing bothered me and I wanted to make a different choice. And perhaps for those pagans, simply gathering outside on a sunny day was nature enough for them. But I wanted more, and I think naturalist paganism in particular would do well to include encouragement toward regularly assessing and improving one’s actions in relation to one’s beliefs when it comes to nature and the environment.

Here’s where a lot of people run into the sticky trap of dogma. I’m betting a lot of readers have, like me, run into that one variant of Wiccan who interprets “An if harm none” to mean “don’t eat animals!” and then insists that only vegetarians can truly be Wiccan. That’s just one example of where personal choice turns into an attempt to sic one’s dogma onto others. I don’t want to advocate that here. Just as each person’s spiritual path varies according to their needs and restrictions, so too are the actions associated with that path dictated by individual limitations and choices.

More importantly, it’s awareness, reflection, and conscious choice that are at play here. I am well aware that the car I drive, even if it does get pretty good mileage, still contributes to climate change and other results of pollution. However, I would not be able to vend my artwork at events, or take huge piles of packages to the post office, or run weekly errands associated with my business, if I didn’t have my car. Or at least it would eat a lot more into my time and lower my income more than what I currently pay for its maintenance and upkeep. But I try to balance that out by keeping it in good working order and not driving it more than I need to, and by walking or taking transit when I can. It’s that consideration and carefully-made choice that is more important than blindly adhering to the idea that if you have a car you don’t love nature enough.

And that brings me to the last question to ponder: What can I realistically change in my life right now to be more in line with my approach to nature spirituality? This is a question we can ask repeatedly–even every day, if that’s appropriate. The answer is likely to change quite a bit over time through growth and knowledge and experience. But that’s part of having a living, evolving spiritual path: you have to give it space to grow. The answers aren’t all set up in one concise book somewhere. They’re organic and they adapt to change much as we do. It’s a challenge sometimes to always be updating one’s path, to incorporate new information and reflections, and occasionally it may be tempting to just find a one-stop-shop for all the secrets of the universe.

But nature isn’t stagnant, and we only fool ourselves into thinking that only religion stands solid. If we are going to truly align ourselves with the currents and courses of the natural world, if we’re going to understand even a bit of what nature really is, then like the rest of nature we need to be prepared to adapt and explore. That means putting down the book of easy answers and “meanings”, and opening our senses to the world around us.

Sure, it’s scary sometimes, but exciting and full of curiosity, too. And I’m right here with you; you’re always welcome to comment or email me with your questions or thoughts as you walk your own path.

Like this:

Like Loading...