It’s festival season again, which means it’s time for one of my favorite pastimes: counting the number of illegal bird feathers I see on people’s hats, jewelry, and rear-view mirrors. Well, okay, to be fair there are plenty of other things I’d rather be doing, but being a naturalist my eye is automatically drawn to the ephemera of the wild. The feathers people tend to pick up most often are pretty easy to identify–usually the wing or tail feathers of assorted raptors and corvids, or more colorful songbird plumage. (I very rarely see the more drab garb of your average Little Brown Job.)

If the owner of said hat/jewelry/vehicle is nearby, I’ll usually follow up my observation by surreptitiously mentioning to them that technically they’re not supposed to have that feather. Responses are usually along the lines of “Wow, I had NO IDEA! Let me take care of that!” with the occasional variant “Well, too bad–I found it and it’s mine, and no one can take it away from me because of religious reasons/finders keepers/etc.”

There’s not a lot I can do about the latter group of folks, but I always hope I’ve made a difference to the former. On the grand scale of wildlife violations, a molted blue jay feather is pretty far down anyone’s list of priorities, and it’s not highly likely that fish and wildlife officials are just going to be bumming around your average pagan or hippie festival. But there’s always that chance that someone is in the wrong place and wrong time with the wrong feather, and not knowing the law isn’t a good defense if an official decides to make an issue of it.

You Don’t Know What It’s Like, Breaking the Law

Law? Yes, that happens to be the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 (MBTA). The text of the law prohibits, within the United States, the “pursue, hunt, take, capture, kill, attempt to take, capture or kill, possess, offer for sale, sell, offer to purchase, purchase, deliver for shipment, ship, cause to be shipped, deliver for transportation, transport, cause to be transported, carry, or cause to be carried by any means whatever, receive for shipment, transportation or carriage, or export, at any time, or in any manner, any migratory bird, included in the terms of this Convention . . . for the protection of migratory birds . . . or any part, nest, or egg of any such bird.”

What’s a migratory bird? It includes almost every wild bird in the United States, from raptors and corvids to songbirds and waterfowl. About the only birds not protected are non-native species like pigeons (rock doves) and European starlings. There are hunting seasons on a few species, such as certain ducks and geese, and American crows. However, their remains are still strictly regulated; only the hunter who killed the birds (legally!), or someone that they give them directly to, may possess them, and they can’t be bought or sold.

What this all boils down to is that unless you have a scientific permit, you cannot legally possess the remains of any migratory bird, even naturally molted feathers. A common misconception is that Native Americans (federally enrolled or not) are exempt, but this isn’t the case. The only exception there is to a different law, the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act of 1940, and even then enrolled tribal members must be on a waiting list to get feathers and other remains from the National Eagle Repository.

The Birth of the MBTA

If you were to walk down the street in any American city in the late 1800s to early 1900s you would likely see an abundance of birds, dozens of species within just a few hundred yards of each other. The catch? They’d all be dead, resting on fancy women’s hats as individual feathers, wings, or even entire bird skins. From common songbirds like robins and cardinals to more remote species like sage grouse and goshawks, all would be on display for the sake of fashion.

Now, there’s nothing wrong with feathers as adornments. But at the time there was no regulation of how many feathers (or birds) could be taken in a season, which meant commercial hunters could kill millions of birds a year with no limits. This is the time period in which we lost the passenger pigeon and the Carolina parakeet, among other now-extinct species. And we almost lost many others along the way.

Probably the best example of the excesses of the time was the great egret. Egrets develop a particular sort of fine plume during breeding season, and maintain them while still nesting. (You can see a particularly lovely example on the cover of Faith No More’s album, Angel Dust.) By the time the birds naturally molt these feathers they’ve gotten ragged and dirty from months of nesting and other wear and tear, so they weren’t sufficient for the hat trade. Plume hunters therefore would go into the wetlands and kill one or both adult egrets, often while they were still incubating eggs or caring for young. For the sake of a few feathers, both parents and up to four young could die. Egret numbers plummeted.

Enter the MBTA

The early 1900s saw the passage of the first laws to protect wildlife and trade in their remains. The Lacey Act of 1900 made it a federal offense to transport illegally acquired or possessed species over state or national lines, but it was sometimes difficult to enforce. The Weeks-McLean Act of 1913 set hunting seasons for birds, to include prohibiting hunting in the spring during nesting season, but it was found to be unconstitutional.

The MBTA improved on what the Weeks-McLean Act was trying to accomplish. It laid out firmer and more widespread restrictions on the killing and possession of migratory bird species. The Act was based on treaties the U.S. made first with Great Britain (representing Canada), and then later Mexico, Japan and the then-Soviet Union. Its goal was to protect all species of wild native bird that migrated between the U.S. and any of those countries.

The feathered hat trade had slowed down significantly with the rise of World War I; the fancy excesses of the Victorian and Edwardian eras were replaced by more sober practicality as participating countries had to tighten their belts to pay for the materials of war. The millinery industry, market hunters and others dependent on the feather trade were already hurting financially, and the MBTA was a final nail in the coffin.

But the trade-off was worth it for the birds. The great egret and many other species rebounded to healthier population levels. Today songbirds are a common sight even in urban areas, and raptors glide over the landscape (helped along by the ban on DDT in the 1970s). Waterfowl are recovered enough to allow hunting seasons, though these are carefully regulated.

Sadly, the MBTA came too late for some species. The ivory-billed woodpecker may have lasted longer than the Carolina parakeet, but low numbers coupled with continuing habitat destruction led to the almost-certain demise of this bird. The story is the same for Bachman’s warbler, the heath hen, the New Mexico sharp-tailed grouse and the dusky seaside sparrow, as well as many Hawaiian native birds whose MBTA protection came only with Hawaii’s statehood in 1959.

Migratory Birds and the MBTA Today

Despite the successes of the MBTA, there are still good reasons for it to remains on the books in the 21st century. One third of North America’s migratory bird species are at serious risk of extinction. Habitat destruction, climate change and pollution events like oil spills have devastated both bird populations and their nesting and wintering sites. Predation by domestic and feral cats accounts for the deaths of hundreds of millions of wild birds every year. Our birds aren’t out of the woods yet.

Still, some people question the strictness of the law, particularly in cases of building infrastructure for alternative energy and other human endeavors. Some of the questions I’ve heard everyone from taxidermists to festival attendees as are: Why should someone face fines and possible incarceration for picking up a crow feather? Why can’t there be some limited season on non-game birds, especially those that are common like gulls? And why on earth are Canada geese, which are considered pests in many areas, still protected?

I know it’s frustrating. There are plenty of times when I’ve had to pass by beautiful molted feathers on the ground, no matter how lovely they might be in my art or personal collection. (And those human-acclimated Canada geese can be MEAN!)

But ultimately, I’m on the side of the MBTA and the scientists who are in support of it. For one thing, it’s next to impossible to tell the difference between a naturally molted feather and one that was stripped from a poached carcass, so lifting the ban on found feathers would almost certainly have devastating consequences. Remember, too, that 1918 was just under 100 years ago, a blip in ecological time. Forests felled that year are still recovering, so why should we expect the forests’ inhabitants to be completely in the clear?

Most of all, I support the MBTA because it’s still having positive effects. Do we need to discuss situations like making exemptions for wind farms and the like? Of course. But wind farms are much more necessary than taxidermy mounts or feathered hats, and I feel that those of us who create non-essential (but pretty!) things out of feathers, hides and bones should leave the exemptions to the necessities. We have plenty of alternatives–just look at the beautiful variety of feathers available on heritage chicken breeds, for example!

And if your concerns are of a spiritual nature, I have found over many years of experience that the totems and spirits of endangered species appreciate the substitution of more common feathers and remains in lieu of their own. Really, what better offering can you give an endangered animal totem than protection of its physical counterparts? You don’t actually have to have a raven feather to connect with Common Raven; a dyed goose feather will do just as well (though be sure to thank Domestic Goose as well!)

You can find out more about the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and other relevant laws at my Animal Parts Laws Pages.

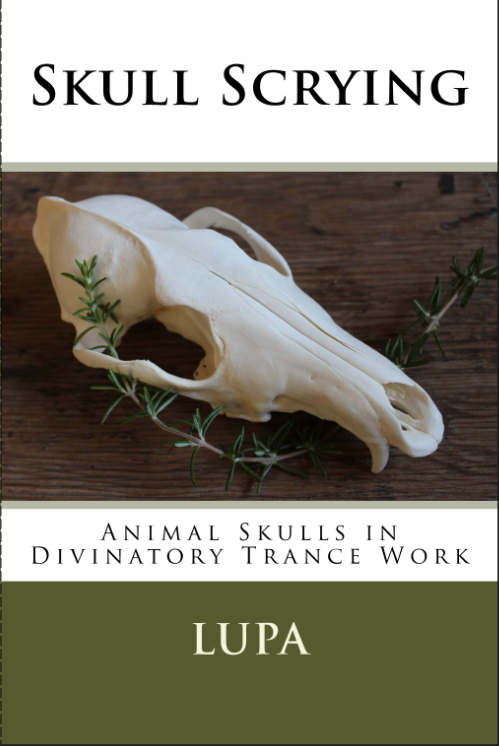

Did you enjoy this post? Consider picking up a copy of my book, Skin Spirits: The Spiritual and Magical Use of Animal Parts, which includes discussions of legalities and ethics along with rites and practices for treating hides and bones with respect on a pagan path.

Like this:

Like Loading...