“Hey, can you make me a pouch, but with fake fur instead of real?”

“I really like your animal headdresses, but can you make one with a taxidermy form and glass eyes in it?”

“Have you seen those resin rings with moss in them? I bet you could make an even better one!”

These are just a few of the suggestions I’ve gotten over the years as an artist. And I really do appreciate when people try to turn me on to new ideas, materials and the like. It shows that they’re paying attention to my work and they want to see what happens when I turn my creativity in a particular direction. (In other words: please don’t stop making suggestions just because of what I’m about to say in this post!)

Eco-Art and Styrofoam

Some of these ideas work really well. Others…well…they don’t even get out of the starting gate. Some of them are axed due to the limitations of physics (real, triple-curled ram’s horns are very heavy and don’t work for the sort of headbands I use–and also my neck says ouch!) Others are no-go due to legalities (sorry, I can’t make you earrings with real raven/crow/hawk/blue jay/owl feathers since it’s illegal here.) And some, like the suggestions in the first paragraph of this post, I opt out of because I don’t feel they’re going to help me create more eco-friendly artwork.

Some of these ideas work really well. Others…well…they don’t even get out of the starting gate. Some of them are axed due to the limitations of physics (real, triple-curled ram’s horns are very heavy and don’t work for the sort of headbands I use–and also my neck says ouch!) Others are no-go due to legalities (sorry, I can’t make you earrings with real raven/crow/hawk/blue jay/owl feathers since it’s illegal here.) And some, like the suggestions in the first paragraph of this post, I opt out of because I don’t feel they’re going to help me create more eco-friendly artwork.

One of my biggest challenges as an artist and an environmentalist is finding eco-friendly art supplies. As with everything else in our industry-heavy society, most art supplies have been created solely with human need in mind; the environmental effects are much a much lower priority, except where regulations have induced manufacturers to comply with certain standards. Therefore our art supplies are full of plastics and other nonbiodegradables, along with a host of synthetic chemicals, unsustainably mined metals, and other environmentally unfriendly components.

So the very last thing I want to do is to add to that. I’ve had a LOT of people criticize my use of real fur and then suggest I use fake fur instead because it’s supposedly more “eco-friendly”. What they mean is no animal immediately died to make fake fur–but their fakes are made of plastic-based synthetic fibers. These plastics are often derived from petroleum, coal and other pollution-inducing materials, and the entire manufacturing chain for fake fur causes more animal (and plant and fungus) deaths than the death of a single fur-bearing animal. They also don’t biodegrade, and as they break up into ever-tinier bits of plastic they cause even greater pollution and destruction, up to and including killing zooplankton that eat the tiny fragments. (We need that plankton–it’s the backbone of the ocean ecosystem!)

The same thing goes for the polystyrene taxidermy forms on the market, and which people keep insisting I use for taxidermy headdresses. I am not about to take a brand-new chunk of non-biodegradable styrofoam and shove it into the head of a headdress, never mind the additional ecological burden of the hide paste (often polymer-based), plastic fake teeth, and mass-manufactured glass eyes used in the making of taxidermy. As for the resin jewelry? It’s made of acrylic, and I’ll explain why that’s a problem in a minute.

Allow me me make something clear: I’m far from innocent, even as I eschew the above suggestions. While I try to be mindful of my supplies, I’m as deeply embroiled in this system of toxicity as most other artists. Let’s look at a recent piece of mine as one example.

Deconstructing a Fox

This is a fox skull necklace I created earlier this year for an art show. It’s pretty typical of my work–lots of yarn and beads and paint, with real bone as the centerpiece. Pretty eco-friendly, right? Well, let’s dig into that a bit more.

The skull itself came from another artist’s leftovers; it was likely from an animal hunted or trapped for its hide. More people are reclaiming the bones from these animals so that more of the remains are being used rather than discarded. When other artists sell off their supplies or collections I like to buy them up when I’m able to afford to; it keeps me from having to buy new ones, and it lets me put a bit of money in the pocket of an individual who needs to pay the bills.

Bone itself is pretty environmentally neutral, but remember that in this case I coated it in acrylic paint. I use acrylic for all sorts of projects; it adheres well to both bone and leather, comes in a variety of colors, mixes easily and dries quickly. It’s durable enough to be put on drums (with sealant) and it’s inexpensive. It’s often upheld as a good alternative because it’s water-based rather than oil-based, and other than acrylics made with cadmium and other heavy metals they’re relatively free of pigments commonly thought to be toxic. But what about the acrylic itself?

Acrylic is a thermoplastic made from applying heat to certain organic compounds. At least one of which, acrylic acid, is very corrosive to human skin, so don’t think “organic” equals “harmless”! All an organic compound is is a molecular compound containing carbon–many of which can be man-made. Additionally, the craft-grade acrylics I usually use often have vinyl or polyvinyl acetate (in other words–more plastic) mixed in for better stickiness and to cut costs. Both acrylic and vinyl are polymers, which means they’re made of very long chains of molecules. It also means that they’re next to indestructible, and therefore not easily biodegradable. So essentially what this means is when I paint a skull with acrylic paints, I’m putting a very thin layer of plastic on it. Even if I forgo the acrylic sealant (which would add yet another layer or three of acrylic), it’s still a lot of plastic molecules that are eventually going to flake off into the environment, and even tiny bits of plastics can have a devastating ecological effect.

The skull is strung on a necklace made of braided yarn and embroidery thread. I did buy the thread and yarn secondhand, since the thrift stores are full to overflowing with craft supplies around here, and I can get big bags of the stuff for relatively little cash. So I’m able to cut down on the demand for new manufactured goods, but what happens once the cord wears out and has to be replaced? Well, the yarn is–surprise, surprise!–acrylic. The embroidery thread is “mercerized cotton”. What the hell does mercerized mean? In short, it’s a process wherein cotton fibers are wrapped around a polyester (plastic!) core. I can only imagine the chemicals that went into the dyes used to bleach and color these things. Here’s a partial list of what could be in them. The dyes used in clothing, which likely have some overlap with yarn, are supposedly “nonpoisonous”, but again they’re only looking at the direct effects on humans who accidentally ingest them, not the massive environmental effects of the production of these dyes.

Finally, let’s look at the metal content of this piece. The cord is adorned with brass bells and copper beads, both from India, which means more shipping costs like ocean pollution. The copper wire was reclaimed from old computer components, so at least that’s a reclamation. All of these metals were probably mined in less than environmentally satisfactory manners, with resultant pollutants and other damage. Even in areas with regulations, violations of these laws are all too common. While the brass and copper itself may naturally corrode over time, the chemicals used in its mining, treatment, and manufacture into crafting materials likely won’t break down so easily.

Reducing the Impact

I’ve been aware of the environmental impact of my artwork for years. It’s not feasible–or desirable–for every artist to entirely switch to a completely guilt-free medium all at once. An established oil painter wouldn’t do very well to suddenly start making all of their art out of old bottle caps and twist ties. But we can look into ways to more organically shift our materials in an environmentally conscious direction.

I’ve been aware of the environmental impact of my artwork for years. It’s not feasible–or desirable–for every artist to entirely switch to a completely guilt-free medium all at once. An established oil painter wouldn’t do very well to suddenly start making all of their art out of old bottle caps and twist ties. But we can look into ways to more organically shift our materials in an environmentally conscious direction.

–Secondhand first (and local when new)

This is currently my most common solution to the environmental conundrum. Most of my acrylic paints are secondhand, either from SCRAP, local thrift stores, and even free boxes on Portland curbs. These sources often yield other treasures, like perfectly good paintbrushes, beads, yarn and related materials. And, as I mentioned earlier, I try to buy hides and bones secondhand as often as I’m able. I don’t remember the last time I actually bought something from Michael’s; the last new thing I bought was a couple of tubes of paint (acrylic and tempera) from the local family-owned art supply store around the corner from my apartment.

–Use it up, wear it out, make it do…

I throw very little away when it comes to my art. Tiny hide scraps and ends of thread end up as pillow stuffing. Old paint brushes get repurposed into assemblage materials. I don’t get rid of a tube of paint until I’ve squeezed the past tiny bit out of it. I also don’t buy things I don’t need. I have one pair of jewelry pliers I’ve been using for almost twenty years. While certain parts of my art might be a little easier if I owned an airbrush, I prefer to keep making the acrylics dance to my tune.

–…or do without

Sometimes I just say no, like with the taxidermy headdresses and resin jewelry. I already make awesome headdresses and beautiful jewelry without adding more to my plastics load. I don’t need to jump onto the next trendy-trend, especially if my conscience really isn’t okay with it.

–Finding alternatives

For the past few years I’ve been wanting to experiment with better alternatives to some of my materials. It’s only been recently I’ve started trying these new media, though. My most recent experiment has been testing tempera paint to see how it compares to acrylics in my usual creations. I’ve thought about making paints and glues from scratch (like these Earth Paints that my friend Autumn reminded me about recently), though I do have to be mindful of my time restrictions and the relatively small amount of paint/glue I use in one project. But it’s still an option on the table.

I also have to make sure the alternatives aren’t just as bad as–or worse than–what they’re replacing. I occasionally use hemp cord instead of yarn for necklace cords. Trouble is, it’s a lot harder to find it secondhand, which means I almost always have to buy it new. That means I’m contributing to the more immediate demand for this resource, which is often manufactured overseas and then shipped over here with a heavy environmental toll for the trip. And like other industrial crops, hemp is grown as a monocrop, which means miles upon miles of natural habitat chewed up for fields that only produce hemp, wildlife displaced and native plants exterminated. So in this case, at least, I figure secondhand yarn is the better option for me.

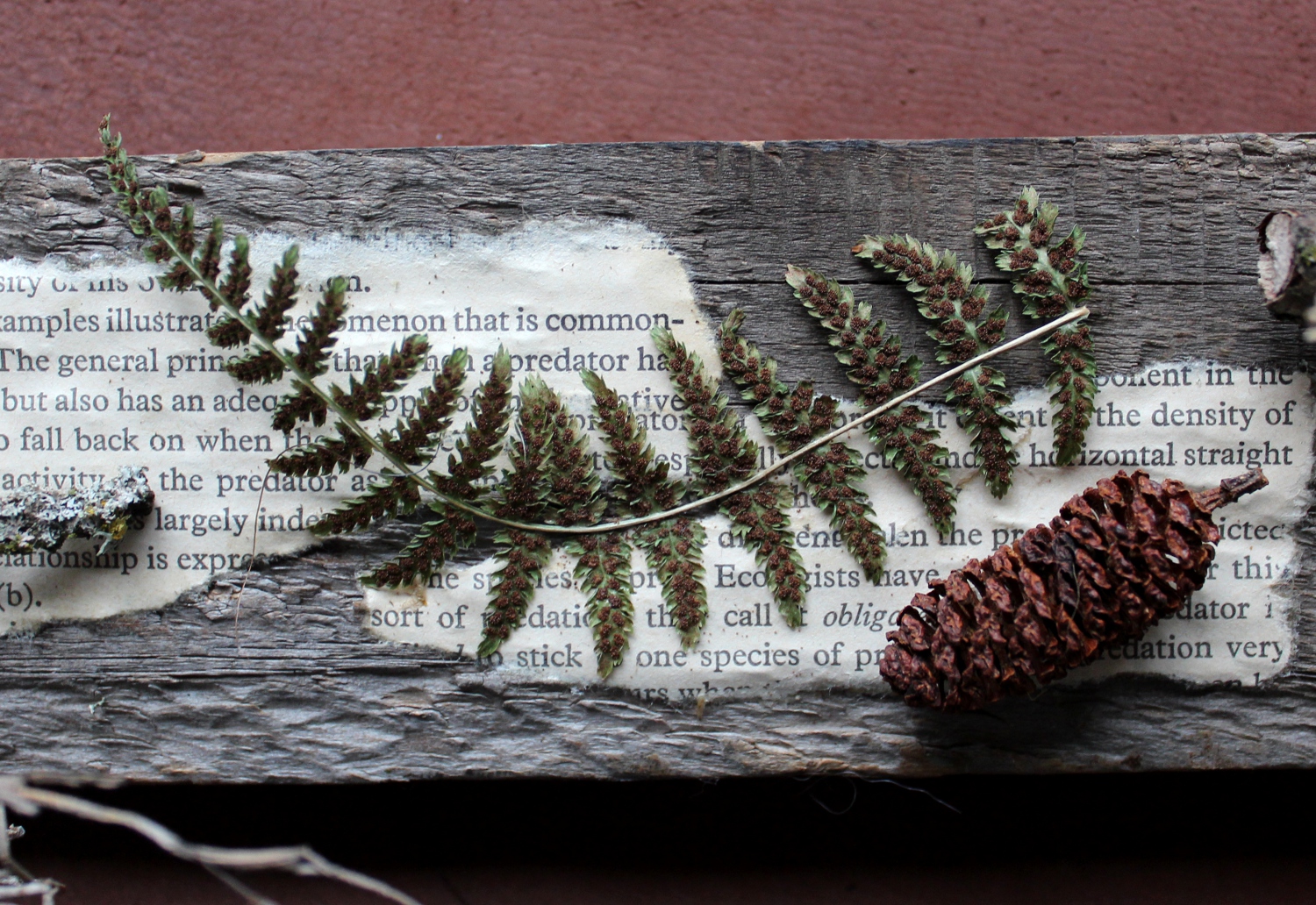

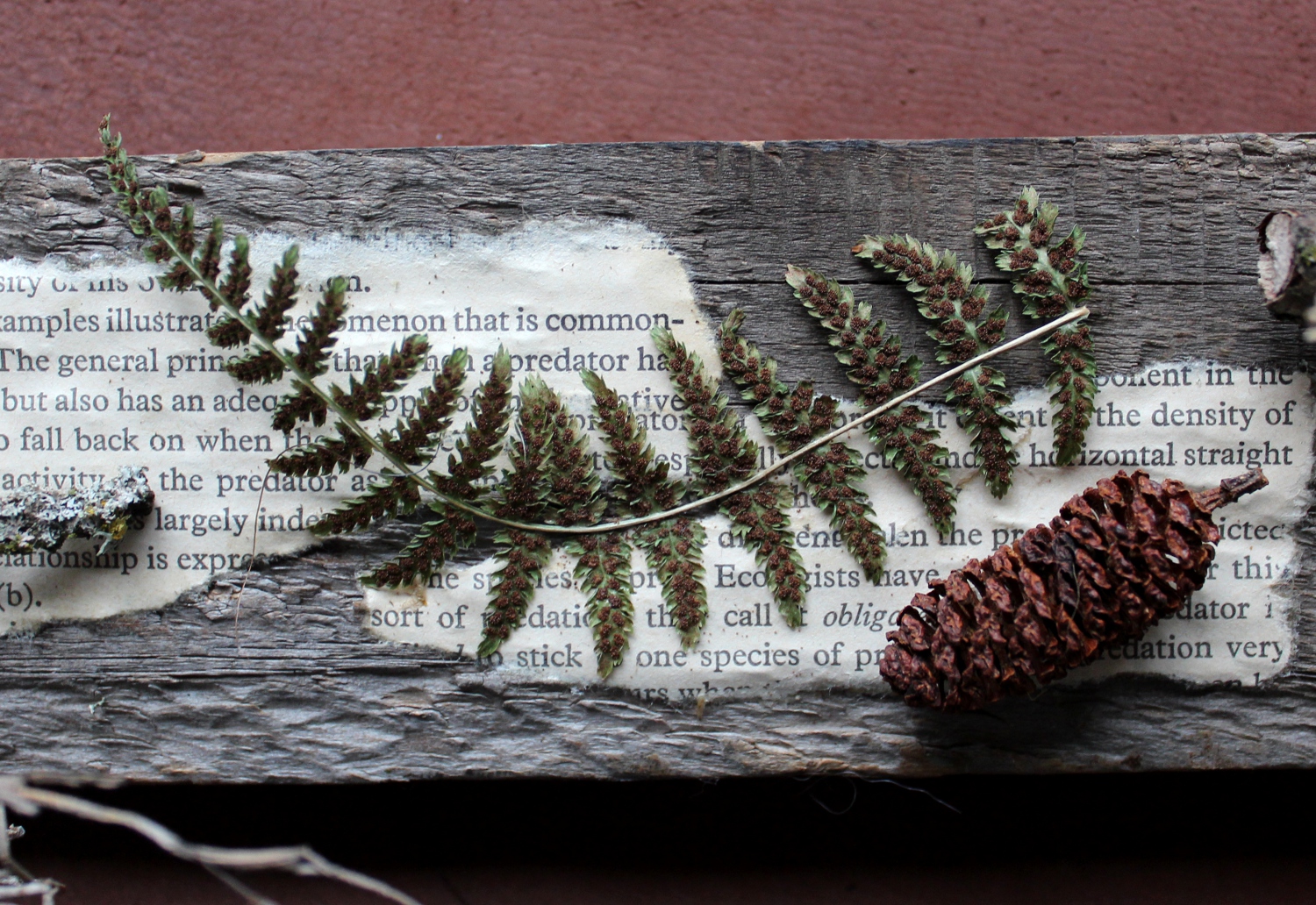

–Don’t take too much

It’s become en vogue in recent years to incorporate pine cones, seed pods, dried leaves and other such things into artwork, particularly assemblage and jewelry. Unfortunately, this can be devastating to a local habitat, especially if over-harvesting is done on a regular basis. I tend toward materials that aren’t in any danger of being extirpated; after a windy day I walk around my neighborhood and pick up sticks covered in lichens since they’re just going to end up mulched anyway. I leave nettles alone, though, because in Portland the numbers of red admiral butterflies have plummeted in recent years thanks to overharvesting of nettles for food by would-be back-to-nature fans. (Thanks to Rewild Portland for being honest and spreading the word about that unintended consequence!)

–Give back

Nothing is better than reducing your impact. But everything we do in this tech-heavy, resource-hungry culture has a negative effect on the environment, and so sometimes we can help through a sort of rebalancing. In addition to trying to be a more mindful artist, I give funds (and some volunteer time) to environmental nonprofits who can do more to make big changes than I can. I’m not a lobbyist, I don’t have the paperwork to go into parks and start planting native species, and I don’t have money to buy conservation easements. But I can at least funnel some of my income towards the people who do these things and more. And while I’m a busy self-employed person, I at least have enough schedule flexibility to do some volunteering now and then, whether it’s litter pickup or water testing.

When it comes to art and the earth, there are no quick and easy answers; using fake fur won’t automatically make you a more eco-friendly artist than I am. But if we keep having these conversations on what’s the best alternative for our own needs, and if we keep sharing information and resources, we can start shifting the attitudes that have led to our primary options being toxic and destructive, and move toward a more mindful and responsible way of creating our art.

Like this:

Like Loading...