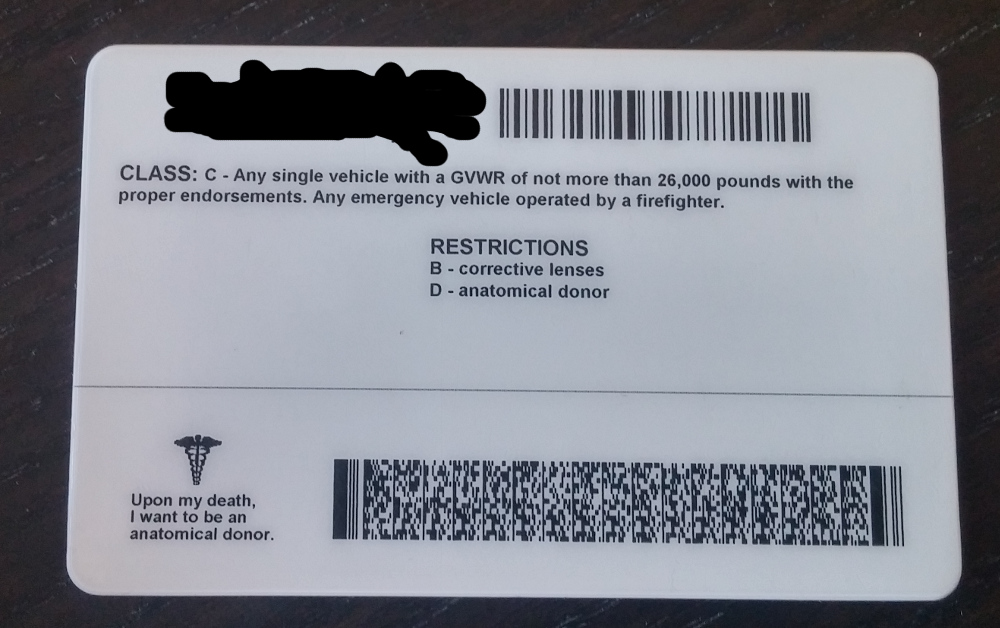

I am an organ donor. Or at least a potential one, in the event of my death. I’ve been signed up for over a decade through my various state driver’s licenses. I’m also on the bone marrow donor registry at Be the Match. I haven’t yet been a match for anyone, but I’m there for the call if they need me. (For what it’s worth, they really need people of color to increase potential donors for non-white patients, since white people like me are less likely to be a match for non-white donors thanks to tissue typing. But I encourage anyone who can join to do so, regardless of your race.)

I consider it an important part of my spiritual path to be a potential donor. I’m not especially invested in any particular idea about the afterlife, if there even is one. All I have guaranteed is the here and now, and what I have here and now is a body that I borrowed from the Earth. Every atom in my body came from food I consumed, water I drank, air I breathed. And when I die, I’m going to have to give it all back; I’m a huge proponent of green burial, by the way, and I’d like a spot at Herland Forest.

But not all of me may end up in that ground. If, when I die, my organs are still in good enough condition, I’d like them to go to people who need them. After all, I’m certainly not going to need them. I’ll be dead, and the worms and bacteria and other little critters won’t care that there’s no liver, or I’m missing an eyeball or two. I could selfishly say that since I am against embalming I refuse to allow any part of my body to be embalmed, and therefore refuse to be a donor on the grounds that it’s likely when the recipients die they’ll end up full of embalming fluids–to include my old spare parts. But as I said, that’s selfish, and I’ll sacrifice a few pieces if it means someone else gets to enjoy this world a little longer.

I’m not at all worried about not making it into some possible afterlife because my body wasn’t complete. Do soldiers who lose body parts in combat not get to go to the next life? What about tradespeople who end up losing a finger to machinery, or someone who had their original teeth knocked out in an auto accident? Hell, what about pagans who donate blood and plasma? I mean, really, we’re shedding hair and skin cells all the damned time, and we aren’t able to vacuum them up again, store them in bags and then take them with us to the grave. (Ewww. No, really, ewwww.)

Loss is normal. Other animals run around in the wilderness all the time with missing toes, shortened tails, cropped ears from fights, accidents, frostbite. Our medical technology just allows us to save more damaged bits and parts. The idea that only someone with a “whole” body gets to go to the afterlife just seems antithetical to reality. I mean, I had a large lipoma removed from my hip when I was seventeen. I’m sure it got sent to an incinerator (if it wasn’t plopped into a jar of preservative as a study specimen for students). It left a pretty big scar (which, quite honestly, I think looks really damned cool.) I also had my wisdom teeth removed a few years later. Am I automatically denied an afterlife, if such a thing even exists? Better to bank on what I know I have for sure–this life, and this world–than gamble valuable resources on the idea that there’s something after death and that somehow the integrity of my borrowed, physical body matters there.

I’ve heard arguments that organ donation is against environmental ethics. I am keenly aware of the fact that we have 7 billion humans and counting on this planet; it’s one of the biggest reasons I chose not to have children. Some of the population rise is because people are living longer overall. Organ donation helps facilitate that, though it’s hardly the biggest factor. I don’t think helping organ recipients live a few years longer (or even decades, as we improve post-transplant medicine) is that big an impact compared to how poorly people use natural resources. We could be a lot wiser with our consumption, make birth control and information on how to use it universally available to lower the birth rate, and make room for a few successful organ recipients while we’re at it.

I’ve also seen it said that organ donors are “cheating death”. Well, so what? I cheated death several years ago. I had a nasty case of diverticulitis that turned into peritonitis that put me on 48 hours of IV antibiotics, and I likely would have died had I not gotten that medical attention. Should I have just let nature take its course and died at the age of 31? Taken a chance on some herbs maybe working quickly enough to kill the fast-moving infection in time? Would you prefer I wasn’t here? And would you like to tell organ recipients that they should have died instead? Because that is what I hear people say when they say organ recipients cheat death.

Finally, I feel a responsibility toward other humans to make what resources I am no longer using available to them. It’s a little more complicated than dropping unwanted clothing off at a shelter or taking excess art supplies to SCRAP, but the concept is the same to me. Some people refuse to donate because they think their organs will be wasted on those who in their mind don’t “deserve” them, or who won’t survive long post-transplant. Sure, my heart may go to someone who end up dying six months later because it just didn’t “take”. But it might also go to someone who gets to live another decade, in which they may finish that book they were writing, plant trees for future generations to enjoy, or simply bask in a few more glorious sunsets. My corneas may end up with someone who dies in an auto accident three years later–but then given that over 90% of cornea transplants are successful, they got three years of sight they wouldn’t have had otherwise. No one knows for sure who will get my spare parts, and as I’d be dead I’d have no control over it. But isn’t death the ultimate act of losing control anyway?

As a naturalist pagan, my primary loyalty is to this world and the beings I share it with. And it’s because I feel so deeply for all of this that I want to make the best use of what I have to offer, down to my very mortal remains. You may have very valid reasons for not being a donor, and I respect your reasons, and if applicable your disagreement. But for me, organ donation is just one more part of my spiritual path, one that will continue my journey beyond death itself–even if I’m not around to see it happen.

Go here for information about being an organ and tissue donor in the U.S.

Go here for information on being a bone marrow donor in the U.S.

Did you enjoy this blog post? Want to encourage me to keep writing about various pagan-related topics? Consider buying one of my books, or become my Patron on Patreon for as little as $1/month!