Note: This post was originally posted on No Unsacred Place in 2011, and then later Paths Through the Forests. I am moving it over here so I can have more of my writings in one place.

There’s a recurring dream I have; it started when I was young. In it, I take my form as a white wolf. I’m in a forest, and the forest is burning. The tall pines and fir trees crackle and split in the flames around me, and I can hardly breathe for the stinging clutch of smoke at my throat. Hot embers scorch the pads of my paws. The tops of the trees begin to topple over, weakened by the flames, and the ground is suddenly made more hazardous with smoldering logs. If I could only find my way out…where is my pack?

I awaken suddenly, panting, startled, thrust back into my skin and flesh and bone all too quickly.

Human legend and lore is full of shapeshifters. Sometimes the changes are literal—physically transmuting the body into that of another animal, or even a plant or stone. Sometimes the person may become a breeze, or a waterway. Sometimes the change is conscious and consensual; other times…not so much.

There are other shapeshifters, too. They include those who take on many roles—Lugh Samhildánach (The Many-Skilled), who excelled at any task given, or polymaths like Leonardo da Vinci. Many people, from thespians to cosplayers, take on a new persona when they don particular clothing; we see this in the wearing of ritual regalia in many traditions as well.

Shapeshifting, for some, is only about taking on a role, wrapping a core self with a persona that may be worn or removed like clothing. But in a more ritualized, spiritual setting, shapeshifting is about becoming something other than ourselves.

The idea of stepping outside of the self and into another is often alarming to the Western post-industrial mindset. It brings up inaccurate images of mental illnesses, or at the very least identity confusion. We are taught that each person has only one identity, and while it may be tweaked a bit here and there depending on whether you’re talking to Aunt Mabel or your secret crush or a job interviewer, you’re still supposed to essentially be you.

Yet to be done fully, shapeshifting necessitates a very deep empathy with another being. Most of us don’t empathize beyond emotions; we allow ourselves to feel with another person’s pain, for example. But to really become another being, we have to open ourselves up beyond that, and set ourselves aside.

I am 23 years old, at my very first pagan gathering, a weekend celebration at Brushwood Folklore Center in New York. Night has long since fallen, and I am at the drum circle, with a fire burning brightly in the center. In my hands I hold my grey wolf skin that I have transformed into a dance costume with carefully tied leather straps. I have spent hours practicing dancing in it in my apartment for the better part of a year, but this is the first time I’ve been brave enough to dance in front of others.

I drape the hide over my head, slip my arms through the same holes that lupine muscle and bone once filled, and tie the hide to my head, wrists and ankles. I feel Wolf the totem, and wolf the spirit, slide over me with the hide, and I suddenly feel I am so much more than myself. I step into the lines of dancers circling around the fire again and again, and I—we, the wolves and I—begin to dance. And soon, it is just I, Wolf-I.

We require an Other place to shift into an Other self. It may be Other only in the sense that one’s physical setting has changed—going from work to home, for example. But the Other place may also be the land of dreams, or the spirit world of journeys, or a physical wilderness unlike one’s home territory—or a deliberate ritual setting.The dreamland is often the first place we experience shapeshifting of some sort, due to its universality in our experiences, as well as its mutable nature. The dreamland may alternately be described as the subconscious romping ground of our brains and the cumulative inner landscapes we have inherited from our many ancestors, or entry into an entire world apart from us where we might literally meet our ancestors, among other spirits.

As we grow older and become more integrated into relationships with other beings, human and otherwise, we develop the ability to make subtle changes in ourselves according to present company and setting. The shifts are largely unconscious, and we may only be peripherally aware that they’re happening most of the time. By comparing how we present ourselves in various situations, we can begin to better understand the processes by which we change.

Ritual is a deliberate shift. We put on special vestments, create ritual space, and utilize items that are unique to that setting. We may still remain ourselves, though yet a different part thereof. But some of us also become other beings entirely through invocation and similar rites. While our earlier experiences with shapeshifting may seem to be out of our hands—literally—practice does make perfect, or at least better.

Drumbeats carry me into the journeying state; I can still vaguely feel my left arm pounding the beater against the horsehide drum held by my right. However, it is an arm covered in white fur. The fingers are shorter, stubbier, ending in claws, and growing less and less human as I watch. Were I to return to my physical form, I would find myself just as human as ever. But here, in the spirit world, my human form melts away—wolf-form is easier to travel in, easier to protect myself in. And there are beings who will only speak to me in this form, too. Humans can be scarier than wolves, you know.

Consciously shapeshifting into another being, especially with the aid of a representative of that sort of being, can be one of the most powerful acts of magic. The effects may be wide-ranging.

On an individual level, we may go places we couldn’t otherwise, in spirit and in emotion and in mind. We can break out of personal ruts, learn valuable lessons from the beings we become that we can then bring back to our human lives, and strengthen our imaginations and other creative spiritual skills.

We also stand to learn more about the world around us, to be more aware of the importance of other beings and places. It is harder to disregard someone that you have been yourself, even for a short while. Indeed, for many people what is most sacred is that in which we are most able to immerse or surrender ourselves.

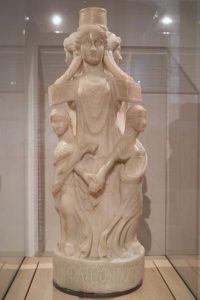

Those sacred things that allow us to temporarily blur or remove our boundaries vary from person to person. I have limited my anecdotes to my experiences with Wolf and wolf spirits—partly due to tradition, and also to show that it’s possible to work with the same energy/being in different forms of shapeshifting. But it is quite possible to connect with a variety of animals, plants, stones, waterways, places, and yes, even buildings and statues and parks, through shapeshifting. This holds true whether it’s on an individual scale, or something as potentially elaborate as Joanna Macy’s and John Seed’s Council of All Beings.

In my next post, I’ll be offering more practical information on methods of shapeshifting, with a special emphasis on practicing it as a way of connecting with other beings.

Did you enjoy this post? Please consider supporting my work on Patreon, buying my art and books on Etsy, or tipping me at Ko-fi!