It’s Earth Day, and while my blog tends to be pretty eco-centric year-round, I wanted to write today about a particular topic that comes up a lot in paganism, particularly among newcomers: ritual tools. Now, it’s been said many times by many people that you don’t actually need tools to be a pagan. I do agree that you can perform rituals open-handed, with nothing but yourself and the spirits/gods/energy you’re working with to make things happen. However, some people just like having the tools themselves; they help heighten the ability to suspend disbelief. And some people feel their tools have spirits of their own, thus making them allies in ritual.

–The wax is probably petroleum-based, which means it benefits from fossil fuel subsidies from federal and state governments. The chemical company that developed the dye might also have gotten subsidies as well. This means that these companies are getting money for free, out of people’s taxes, and therefore can sell their products more cheaply. These companies are also usually not required to pay for the effects of the pollution that’s a byproduct of their processes.

–The candles were likely to have been made by underpaid, sometimes abused workers in a factory in China or another East Asian country, with inadequate protection against the chemicals and machinery being used. There’s a good chance that any chemical byproducts of the process are not properly disposed of, and may just be dumped directly into the nearest river, saving them the cost of paying for safer options.

–They were shipped en masse on a boat from their country of manufacture to wherever you are, again using subsidized fossil fuels. The shipping company doesn’t have to pay for the pollution their boats cause to the ocean and the air, so they can keep their costs down.

We don’t have a solid number on the real cost of pollution from the manufacture of these candles, but suffice it to say you’re getting your candles cheaply in part because the entities who made them and their components are passing some of the cost on to the environment. And we add to that, too, any time we burn candles made with noxious chemicals that add to air pollution in our homes and elsewhere. We speak with our dollars when we buy these cheap things–we say “We don’t care, so long as we save a few bucks in the name of practicing a nature religion*”.

So what’s a pagan to do when money’s thin on the ground? Here are some options.

Use What You’ve Got

These are just a few ideas based on one particular set of ritual tools; you can get pretty creative depending on your needs, so treat it like a grand scavenger hunt! (Just make sure that you’re using only your stuff, or that you ask permission to use anything that belongs to someone else.)

Secondhand First

I am a huge fan of thrift stores and other secondhand shops. Sadly, here in the U.S. there’s a lot of consumerism, with much more stuff being produced for our demands than is absolutely necessary. I wrote a few years ago about the immense amount of clothing, housewares and other discarded stuff I found at just one Goodwill outlet store in just one city, and wondered how much more goes to waste every day. A lot of it is perfectly serviceable, too. I could easily build a dozen altars with the items found in one thrift store.

Yet there’s this unfortunate superstition floating around paganism that somehow you can’t cleanse secondhand items, that the histories they have will linger with them and will always taint them as ritual items–but of course, all a brand-new item needs is a quick cleansing! I call bollocks on that one. If you can purify a new glass bowl that’s been made in a sweatshop soaked in human suffering and death, created from materials that cause great devastation to the natural environment, and conveyed to your town while leaving a trail of fossil fuel pollution behind it, you can damned well purify the energy of a similar, secondhand glass bowl that sat on someone’s grandmother’s dining room table with wax fruit in it for thirty years. Most of my ritual tools over the years were secondhand, to include items that other practitioners used in their own rites, and I never had a problem making them ready for my work.

So get over that superstition, and start thrifting! You never know what kind of cool stuff you may find. (My only caution is that it’s really easy to come home with a cart full of secondhand tchotchkes for cheap, which may put shelf space in your home at a premium.)

Foraging At Its Finest

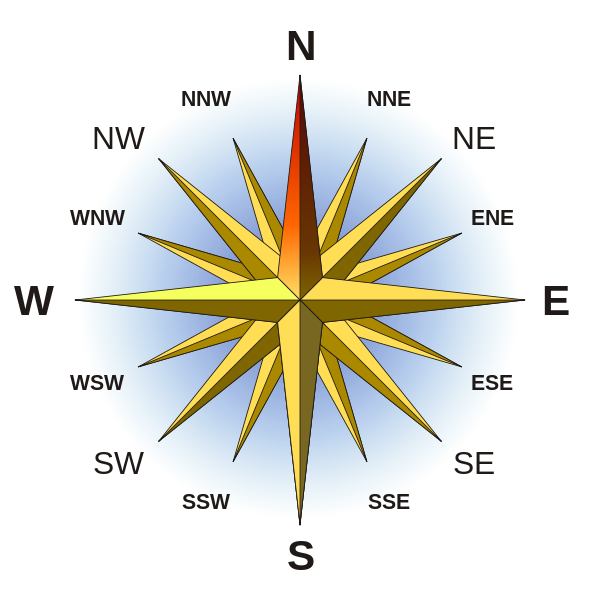

Many nature pagans like having sticks, stones and other natural items in their homes to remind them of what they feel is sacred. In fact, you can make your entire array of ritual tools from things you found outside. If you work with the four cardinal directions and elements, for example, you might have a stone in the north, a feather or bit of dandelion fluff in the east, dried wood or moss as firestarter in the south, and a vial of rain water in the west. The best part of all this is that, other than some containers for things like water, it’s all free.

Many nature pagans like having sticks, stones and other natural items in their homes to remind them of what they feel is sacred. In fact, you can make your entire array of ritual tools from things you found outside. If you work with the four cardinal directions and elements, for example, you might have a stone in the north, a feather or bit of dandelion fluff in the east, dried wood or moss as firestarter in the south, and a vial of rain water in the west. The best part of all this is that, other than some containers for things like water, it’s all free.

Do keep in mind there are certain legal and other restrictions. Federal and state parks in the U.S., for example, prohibit the collection of any natural items found within the park without a permit (some cities do this as well). You’ll need to ask permission when foraging on private property. And some items, such as some animal parts, are illegal to possess regardless of how you got them; most wild bird feathers in the U.S. cannot be possessed, even if they were naturally molted, as one example. (You can access my database of animal parts laws here.)

Grow or Make Your Own

DIY is a wonderful thing. Not only do you get to cut costs, but you get to gain skills, too! For example, some folks like to use herbs in their spells and other magic, and luckily a lot of these herbs can be easily grown, even in a pot by the window. If you worry about having a black thumb, there’s plenty of information on the internet about how best to care for a particular kind of plant; the most common ways to kill your herbs is through too much or too little water and sunlight, the wrong sort of soil or not enough fertilizer, and disease or parasites. If you notice a plant isn’t thriving, you can research online or in books at the library what the possible causes may be, and you can ask garden shops or people on gardening forums for advice.

Other tools can be homemade, too. If you want to have a permanently decorated altar, maybe with a scene depicting your patron deities or symbols of the four cardinal directions, you can paint a secondhand table with acrylic paints**, or carve or burn the designs if the table’s wood. A well-worn broom can be decorated with dried flowers and ribbon, and even re-bristled with straw and other plant materials. A particularly sturdy branch may make a nice wand as-is, or you can choose to decorate it to your preferences.

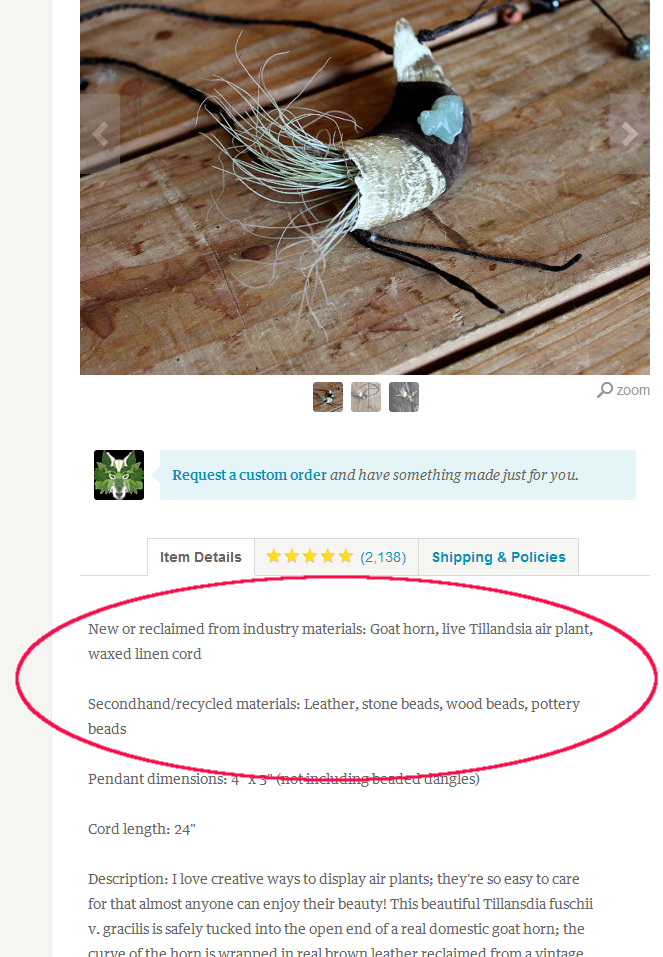

Support Local Artisans

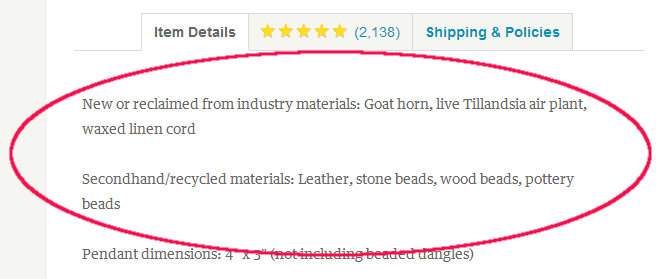

You’re always welcome to ask an artisan about their materials. I talked earlier about cheap, petroleum-based candles from the dollar store; however, there are candle-makers who specialize in eco-friendly alternatives like beeswax and natural dyes, and who avoid candle wicking with lead in it. And the same goes for everything from ceramics to woodworking to paintings; usually there’s somebody who specializes in greener materials out there.

(Shameless plug for my own recycled hide and bone and other natural materials art here, though there are many artisans within the pagan community and elsewhere whose works would be lovely ritual items. Try Etsy, Artfire, and Storenvy for some possibilities.)

Conclusion

I hope now that you see that buying ritual tools on a budget doesn’t have to feed into environmentally harmful processes and practices. In fact, taking care in one’s shopping choices can be an act of spiritual devotion in and of itself. If you feel nature is sacred, then let that speak not just through your rituals and special moments, but in your everyday actions as well.

* With the understanding, of course, that not every person who identifies as a pagan focuses their paganism on nature, and there are some pagans for whom the gods, for example, are central.

** While not without their pollutants, acrylic paints are some of the safest paints that are easily obtained commercially. There are more eco-friendly recipes for homemade paints out there, but acrylics are best if you don’t want to go quite that far in your DIY-dom.

*** The effectiveness of a tool, by the way, is not in how pretty it is or how perfectly crafted. Even if you don’t think you’re an artist, it’s the intent behind the creation that matters. So don’t let that get in the way of making your own tools if you’re so inclined.