Just a quick reminder that I still blog over at Paths Through the Forests, the Patheos blog that I share with Rua Lupa. My newest post there, “The Pagan Ape“, went live this morning. In it I discuss our detachment from nature, the effects that detachment has, and what I feel our responsibility as pagans and humans may be to the planet. Read the post here!

Category Archives: Anthropocentrism

Totemism 201: Why Going Outside Matters

My apologies for the lack of posts as of late. February into March is generally a busy time for events in my vending and speaking schedule, and I’m just now entering a period where I’ll mostly be at home. I still have plenty of other things going on here in Portland, and the Tarot of Bones is still eating my life, but if all goes well there’ll be more blog posts. In my last post I said we were going to talk about a different topic. I’ve got one that’s really prominent in my head right now, though, so I’m going to cover it instead.

So in my travels over the last several weeks I’ve tried to get out into wilderness places at least a few times. I went hiking at Ed Levin County Park in San Jose while I was at PantheaCon, and on my way back home I stopped for a few hours to walk and drive around the Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge. Just this past weekend I did a bit of a birding hike at Minnehaha Falls Regional Park while in Minneapolis for Paganicon. All of these were excellent opportunities to appreciate species of wildlife I don’t normally get to see in Portland, and especially to appreciate the spring migration of dozens of species of bird.

I learned a lot in those excursions, but an experience at home helped to solidify some thoughts I’ve had about why this is so important to my totemic path. This morning I woke up just around dawn; my sleep schedule’s been a bit out of whack with all the travel through time zones and whatnot. So I headed into the living room to start checking email, and to enjoy the morning drama at the bird feeders on my porch. I have both suet and seed feeders, and it’s normal for me to get a variety of tiny feathered dinosaurs ranging from scrub jays to pine siskins to Northern flickers coming by for breakfast.

I’ve also recently discovered eBird, a joint effort by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the National Audubon Society. It’s a website that allows you to record your bird sightings, and I’ve been registering my feeder visitors as they show up. One of the entry fields asks for the sex of the bird, if you have that information handy. Some are pretty easy to discern–a male dark-eyed junco in Oregon looks very different from the female, being darker in color. Others, like scrub jays, have little to no sexual dimorphism. I’ve had a few Northern flickers by yesterday and this morning. On first glance the male and female look very much the same–brown with black barring on the back, and a black “bib” and spots on the chest, with either yellow or red shading on the the tail and wings. I wanted to be able to discern whether I had males or females–or both–showing up, so with a quick bit of Google research I found that the males tend to have a red or black spot on their cheeks.

Why is this important to totemism? Because the presence of both sexes indicates the strong possibility of nesting nearby, which means I can also keep an eye out at area trees for nesting holes and, if I’m lucky, young peeking their heads out as they get a bit older. Sure, I can also look up videos and articles about flicker family dynamics, but there’s something about getting to see it in person that I think would make my understanding of Flicker as a totem more full and vibrant.

See, the “meanings” of animal totems (here’s why I don’t like that concept, by the way) are largely drawn from the animals’ behavior and natural history. Scrub Jay was the first totem to greet me as soon as I moved to Portland almost right years ago, and its bold, brash curiosity was infectious as I began exploring my new urban home. Moving is always a stressful experience, even when it’s for positive reasons, and I’d spent a year in Seattle becoming progressively more depressed and unhappy. Rather than sinking deeper into that because I had to start all over in a new place yet again, I found myself drawn out into the world by a brilliant blue and gray bird.

And over the past eight years I’ve made more of a study of the natural history of this area, both Portland and beyond, from geology to climate to the various sorts of flora, fauna and fungi found in each place I’ve explored (and some I’ve yet to set foot in). I’ve deepened my connection to the land that’s embraced me, and I’ve created more substantial relationships with some of the totems here as well. I feel invested in this place and everyone who lives here, and I give more of myself than ever before.

Many totemists, especially newer ones, rely on totem dictionaries and feedback from on-topic internet forums and groups to get their information on what a totem “means” or whether an animal sighting was a message in disguise. While these can be useful at the beginning, eventually you have to drop the training wheels and figure things out for yourself. I’ve long said that what a particular totem tells me may not be what it tells you, and so coming to me and asking “What does Brown bear mean?” or “I saw a blue jay today, what does that mean” is useless. All I’ll tell you is to ask the totem itself, because that’s a relationship between the two of you.

And a big part of developing that relationship involves going outside–or, for those unable to do so, at least watching/listening/etc. from the window. Hell, barring all else there are books and documentaries and websites on all sorts of natural topics. Nature spirituality is meant to be about our connection with everything else, not just the human-dominated portions of the world, and if you only immerse yourself in dictionaries and forums you’re going to miss out on a lot. Going to wilder areas where we’re less of an influence serves to illustrate just how much we’ve affected the world around us, and what we stand to lose if we keep up our destructive ways. You can look at photos and video, but there’s nothing to compare with seeing it with your own eyes if you’re able to. A picture of a clearcut is devastating, but it’s nothing next to actually going out and walking through a devastated landscape where a forest has been torn down, being completely surrounded by shattered trunks and earth scraped bare.

It’s that sort of experience that helped me move from a “all about me” approach to totemism to a more balanced give and take. Totemism isn’t just about us, as I’ve talked about already, and in my next post I’ll be talking about why giving back through offerings and otherwise is crucial to one’s totemic practice.

A master list of Totemism 201 posts may be found here.

Did you enjoy this post? Please consider purchasing one or more of my books on totemism and related topics! They include more in-depth information on working with totems, to include topics not discussed in this essay series.

Announcing My Next Book – Nature Spirituality From the Ground Up: Connect with Totems in Your Ecosystem

[Note: I know I’ve been pretty quiet the past few weeks. I’ve been out of town a LOT–PantheaCon, Mythicworlds, a few out of town errands. I’m going to be gone again next week, where I’ll be at Paganicon in Minneapolis as a Guest of Honor (woohoo!), though in the meantime you can catch me at the Northwest Tarot Symposium this upcoming weekend in Portland. I should be able to get back to some writing later in the month, if all goes well! Also, head over to the Tarot of Bones website to see my progress on that particular giant project–and find out more about my very first IndieGoGo campaign coming soon! Thanks for your patience.]

I am pleased to announce that I have signed the contract for my third book with Llewellyn Worldwide, entitled Nature Spirituality From the Ground Up: Connect With Totems in Your Ecosystem! For those who really enjoyed the bioregional totemism chapters in New Paths to Animal Totems and Plant and Fungus Totems, this book is for you!

Within its pages I offer ways to connect with the land you live on through the the archetypal representatives of animals, plants, fungi, minerals, waterways, even gravity and other forces of nature. Written from a nonindigenous perspective, it offers tools, practices and meditations for those who seek a more meaningful relationship with the land than the consumer-driven destruction all too common worldwide. And it encourages viewing the world through a more eco-friendly lens and inviting others to do the same.

Most importantly, it’s my answer to our tendency to make nature spirituality all about us. Rather than being full of ways to get things from the totems, it’s about forming relationships with them and partnering with them to undo some of the damage we’ve done. While bettering yourself is a part of that, I avoid the all-too-common “Harness the power of your totem to get what you want!” attitude.

I don’t yet have an exact release date, but it’s due to be in the Llewellyn winter catalog, and I’ll keep you posted! In the meantime, just a reminder–I have a perks package on my Patreon where if you pledge at the $25/month level ($35 for non-US folks) for seven months, you’ll get one of my current books or anthologies each month, and at the end of those seven months you’ll be automatically added to the preregistration list for Nature Spirituality From the Ground Up. Then when it comes out, I’ll send you a copy for absolutely free!

Totemism 201: It’s Not Just About Us, Either

Okay, back to Totemism 201! In my last post, I talked about how totemism extends well beyond animals into plants, fungi, and other non-animal beings. One of the main points I made is that we tend to gravitate toward animal totems because they’re closer to us–we are, after all, animals ourselves. I’ve covered the tendency toward anthropocentrism in spirituality before, but I’d like to tie it specifically to totemism in this post.

Pick up any book on totemism, or surf to a website on the topic, and more often than not you’re likely to run into language that suggests that by reading this material you’ll learn how to unlock the secrets of totemic power and get what you need in your life. I recognize a lot of that is due to marketing, because how better to sell a book than to claim it holds the answers to someone’s problems? Unfortunately it seriously limits the possibilities for relationships with the totems, and relegates them to being tools you take out of a bag only when you need them.

There are plenty of folks who manage to move beyond the “gimme” mindset. However, even they may perpetuate language that encourages others to see totems as means to a personal end. There’s nothing wrong with asking totems and other spiritual allies for aid when you need it, but I don’t feel it should be the sole basis for your relationships with them, especially because “I want I want I want” is a very anthropocentric way of going about things.

If you see totems as aspects of the human psyche given animal and other non-human forms, you may wonder what the problem with anthropocentrism is. After all, they’re all in your head, right? Remember that the totems represent their species, and you can still help their physical counterparts. Anthropocentrism has damaged the physical environment in numerous ways, so any effort to see the world in a less human-dominated fashion can help improve the world for everyone.

So how can you begin to remove the anthropocentrism from your totemism?

–Don’t treat totemism like it’s just a way for you to improve your life. Back when I was talking about the potential pitfalls of totem dictionaries, one of the points that I made is that the dictionary format tends to emphasize a quick fix for our problems. Relationship troubles? Take one dose of Lovebird and call me in the morning. Sure, that’s a bit hyperbolic, but it illustrates the problem effectively.

To break out of that mindset, consider how you view the totems you work with. Who are they besides “Solution A for Problem B”? What happens once you get past the stereotyped “what does this totem mean?” Do you see them as friends? Family? Allies? Beings to be worshipped, or admired, or emulated? (It’s okay if you don’t have an immediate answer; it might take a while for you to really conceptualize your relationships with your totems.)

–Be mindful of how you talk about totems, both the ones you work with and in general. Even if you see the totems as independent beings who have a lot more going on than figuring out how to help you get a new job, if you use language like “Totems are here to teach us things!” you’re still perpetuating a more limited view of them. Instead, try talking about the entirety of your relationship with a given totem (or as much as you’re comfortable talking about). When someone asks you what Gray Wolf means (as one example) you might talk about not just things Gray Wolf has shown you, but also what you’ve done for that totem in return, how close you are, how the relationship has evolved over time, other totems Gray Wolf has introduced you to and why, etc. (This all, of course, depends on how much time and space you have to answer in.)

Moreover, encourage discussions on totems that go beyond “What does this totem mean and what can it do for me?” If you part of an online forum or an in-person group about totems, try starting a new topic. If you teach about totemism, even casually, make a point of going into more depth. Ask others about their experiences. Get the words flowing.

–Another way to reduce an anthropocentric approach to totemism is to get out of your comfort zone. As I’ve mentioned before, we tend to gravitate toward animal totems (especially Big, Impressive North American Birds and Mammals) because they’re most familiar to us. Challenging that familiarity helps us and broaden our attention, and moves us beyond our own priorities of personal comfort.

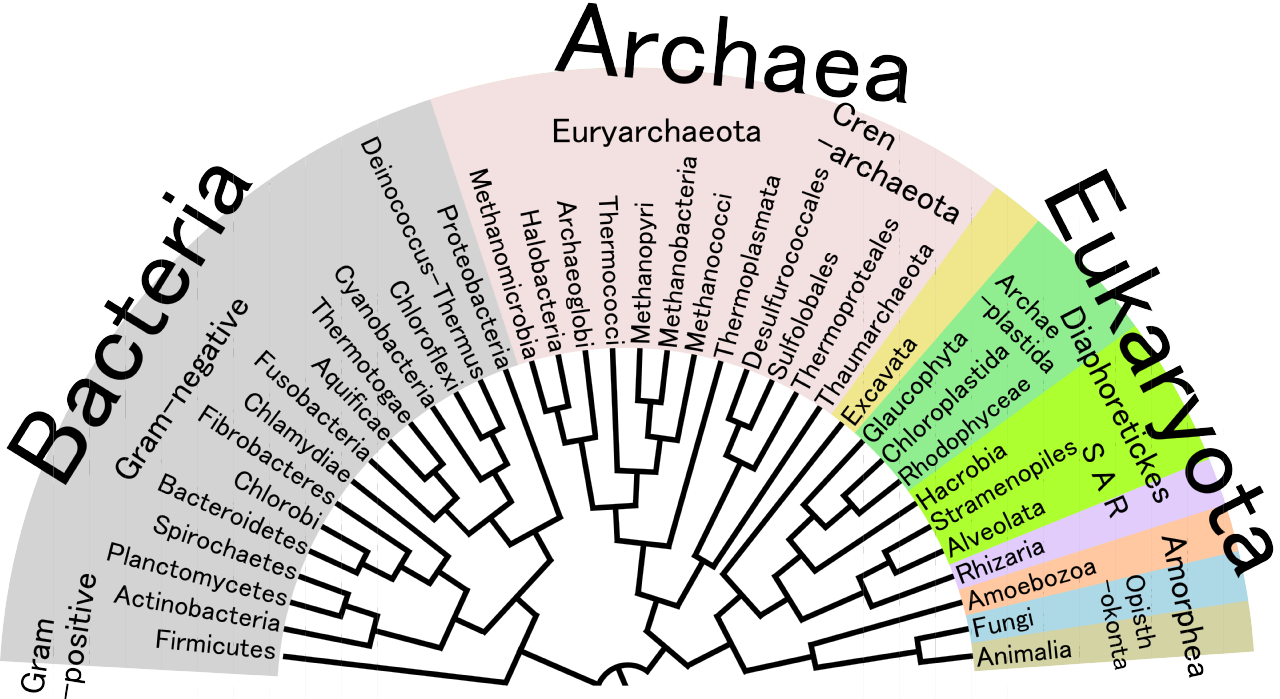

Start one step outside of your comfort zone. If you’ve primarily only worked with mammal totems, try working with a bird or reptile totem. Then take another step, and head into fish territory. Another step may get you in touch with any of a number of invertebrates. Beyond that there are the totems of fungi, plants, bacteria, and numerous other non-animal beings.

The more you put yourself into the mindset of an unfamiliar sort of being, the more aware you become of their priorities. Anthropocentrism relies on human concerns being the most important; by making yourself aware of the concerns of other beings, you loosen the grip of a human-centered worldview.

Those are just a few of the ways in which you can unseat anthropocentrism and move your totemism from “what do I get” to “what can we give each other”. Note that I mention “we” in that last statement. Your goal is not to completely subsume your wants and needs in favor of those of a totem or any other being. The totems don’t need mindless followers, nor do they need people running around in hair shirts, castigating themselves for having any personal needs whatsoever.

Rather, the goal is to regain a mutually beneficial relationship with the totems and their children. We are just one of millions of species on the planet, and we’ve forgotten that. Totemism 201 is about remembering our place, not in a sense of being humbled and chastened and “put in our place”, but in being one among many brilliant, amazing beings in this world.

In my next post I’ll be discussing how Totemism 201 is about approaches rather than practices, and why there’s no secret ritual that will magically make you an advanced practitioner.

A master list of Totemism 201 posts may be found here.

Did you enjoy this post? Please consider purchasing one or more of my books on totemism and related topics! They include more in-depth information on working with totems, to include topics not discussed in this essay series.

Totemism 201: It’s Not Just About the Animals

Alright, let’s try this again. I’ve been neglecting writing for a couple of weeks between running Curious Gallery, and recovering from running Curious Gallery (plus finally making some progress on the Tarot of Bones.) However, I haven’t forgotten about my blog readers, so here’s the next installment in Totemism 201!

Almost all of the material available on totemism concerns animal totems. Their plant, fungus and other counterparts are generally ignored; plants and fungi rarely get much attention beyond being used in herbalism and spells, and other than trees and hallucinogenic fungi few plant and fungus totems are addressed in specific. I’ve already addressed this topic before; here I’d like to talk more about what makes moving beyond the animals a Totemism 201 topic.

–Animals are the easiest for us to connect with.

We are animals, human apes. It’s generally easiest for us to connect with beings that we feel affinity toward, and so we can temporarily adopt the (perceived) mindset of a fellow animal more easily than that of, say, a dandelion or turkey tail fungus. If you look at the most common animal totems, you’ll notice that many of them are large mammals, easier for us to observe and interact with. The less like us we think an animal is, the less likely we are to work with its totem.

It’s even tougher for us to resonate with a non-human being. How do you think like a tree when trees don’t have brains? How do you learn life lessons from a fungus that live underground much of the time and, to our perception, doesn’t even move? Do bacteria and protists even have anything to teach us?

To be fair, it can be more challenging to communicate with a non-animal totem, even when we’re willing and interested. Their priorities for themselves and their physical counterparts are often different than what we might expect; my experiences with Black Cottonwood illustrated that as one good example. And they perceive the world in very different ways; many of them simply see us humans as one of a host of animals thundering our way across the landscape, here then gone in seconds. So they aren’t always as eager to open up to us as some animal totems.

So some people simply stick to what’s easiest and most familiar–animal totems, and more specifically Big, Impressive North American Birds and Mammals. For those who do venture into more seemingly alien territory, there are some potential benefits–read on.

–Non-animal totems encourage us to have a more systemic view of totemism

I’ve often talked about how many people seem to assume that totems simply float over our heads like parade balloons, waiting for us to notice them or call upon them for help. From my experience, they inhabit their own spiritual ecosystem (whether you feel that’s a figment of your psyche or an actual alternate dimension is up to you to decide.) And the plant and fungus totems aren’t just the set dressing for dramas involving the animal totems; rather as in our reality, the totems of all living beings interact with each other in a complex, multi-layered series of relationships.

This is why I’m skeptical when someone says they have only one totem, especially if they’ve been practicing totemism for a while. My experience has been that totems tend to introduce their people to fellow totems they have positive relationships with. Steller’s Jay, for example, introduced me to Douglas Fir, who also introduced me to Douglas Squirrel, Northern Flicker, and several other arboreal totems. Granted, my connection with Steller’s Jay is stronger than that with most of those others, but at least the introductions have been made and can develop organically from there.

Conversely, this also helps me to appreciate the totems as individuals, rather than one-dimensional stereotypes. Seeing how they interact together allows me to learn more about them both on their own and as a community. And it encourages me to value all the totems of an ecosystem, not just the animals.

–They also encourage us to respect living beings besides animals.

That value extends beyond the totems themselves to their physical counterparts. Animals are just one part of a series of complex and multi-layered ecosystems whose intricacies we don’t fully understand. With deeper connections to totems comes a greater sense of responsibility toward their physical counterparts, and many experienced totemists are also environmentalists of one sort or another. What we find as we become more engaged in environmental activism is that it’s tough to be effective when you’re a one-issue activist. Sure, lots of people want to protect gray wolves, but you can’t protect the wolves without protecting the animals they prey on, and you can’t protect the prey if the prey have nothing to eat and nowhere to go. So “save the wolves!” quickly turns into “save the elk”, “save the grasslands” and “save the migration routes.”

There’s a sort of chauvinism that encourages us to see non-animal beings as nothing more than set dressing for our own kind. But when we interact with their totems, and find that they’re every bit as spiritually adept and important as the animal totems, it makes us question that “plants are just scenery” viewpoint. But that’s good for us, really. Even if you strictly work with the animals, it behooves you to respect the plants, fungi and other living beings they rely on to survive and thrive. After all, we’re animals, and without the plants and fungi and bacteria, we wouldn’t be here either. So widen your view a bit, and appreciate your entire community, not just the ones closest to you in biology.

How do you get in touch with non-animal totems (if you aren’t already)? Well, a good start is to ask your animal totems to introduce you to some of the plant/fungus/etc. totems they associate with. Together, the totems can explain why they rely on each other and what sorts of spiritual implications that may have for you. You might also ask the animals which ones they don’t especially care for; there’s lessons to be learned from those more antagonistic relationships as well. (Just avoid calling on totems who don’t like each other in the same meditation/ritual/etc.)

You’re also welcome to simply go outside (in the physical world or in meditation) and see if any non-animal totems try to catch your attention. I’ve found that the plants and fungi, for example, have a tendency to be more subtle in their communications, and so we often miss when they’re doing the equivalent of yelling “HEY!” at us. Slow down, be more observant and receptive, and don’t necessarily look for the same signs you might with animal totems. Rather than seeing a particular plant, you might feel a gentle tug in a particular direction that brings you to that being and its totem. Or you might feel drawn to sit beneath a large tree whenever you go by it, not for the tree’s sake but for the fungus growing on its bark.

As you work more with non-animal totems you’ll learn more of their unique ways of communicating, their priorities, and the things that make them unique. Totemism really isn’t just an animal thiings, and in my next post I’ll talk about why totemism isn’t just about us humans, either.

A master list of Totemism 201 posts may be found here.

Did you enjoy this post? Please consider purchasing one or more of my books on totemism and related topics! They include more in-depth information on working with totems, to include topics not discussed in this essay series.

Totemism 201: Why Species Are Important

In my last post, I mentioned that many totem animal dictionaries tend to categorize totems according to general groups of animals, not individual species. A good example is “Deer”; most of them probably mean “Whitetail Deer”, but there are plenty of other deer species as well with their respective totems. How, for example, might the totem Fallow Deer be different from Whitetail Deer? Or Indian Muntjac? Or Moose (the biggest deer of all!)? These are very rarely, if ever, explored in dictionary-style totem books and websites.

It’s even worse the further you get away from the Big, Impressive North American Birds and Mammals. Last time I talked about how the totems of the thousands of species of spider are often shoved into one “Spider” entry in your standard totem dictionary. Never mind that the life of an orb-weaver like the golden garden spider is very different from that of a ground-hunting Carolina wolf spider, and their totems are quite different from each other as well. The Spider entry extols the virtues of a generic orb-weaving critter, and doesn’t invite a person to get to know the personalities and teachings of individual species’ totems.

About the only time most writers on totemism try to differentiate species is either when the totem is of some singular animal that is the only species in its genus, such as the cheetah, or when they wrongly assume an animal is a distinct species. If there were multiple species of cheetah alive today, no doubt totemic writers would shove all of them into one “Cheetah” category. However, they’d probably still insist on treating melanistic leopard and jaguars (or “black panthers”) as distinct from their spotted counterparts. In truth, the only thing that makes black panthers different from spotted leopards and jaguars is the amount of melanin in their fur; it’s a matter of a genetic mutation, nothing more. The totem Jaguar still watches over all jaguars, whether spotted, solid, leucistic or albino, and the same goes for Leopard and her children. Yet it’s our misinformed bias that makes us think that black leopards and jaguars are somehow more mysterious than the rest–we get stuck on the cover of the book, as it were, rather than diving into the pages themselves. If you think your totem is Black Panther, then figure out whether you’re actually talking with Leopard or Jaguar (or even an extinct species of panther), and go from there.

Why is it so important that we pay attention to species when working with totems, even the totems of similar animals?

–Even the totems of similar species may have very different things to tell you

When I was growing up in the Midwest, I was surrounded by blue jays, rather loud and raucous corvids that are well-nigh ubiquitous east of the Rockies. And while Blue Jay was never one of my main totems, I did have occasion to work with him now and then. He struck me as brash, rude, and sometimes intentionally obnoxious, though still likable. Fast forward to seven and a half years ago when I moved to Portland, and within the first month Steller’s Jay, Blue Jay’s cousin, had enticed me out into the wilderness areas around the city. Steller’s Jay, while also a rather extroverted and loquacious totem, was much friendlier and mellow in personality. Had I just lumped them both into the general category of “Jay”, I might have come up with a totem that was loud and bold, but missed out on the individual traits of Blue Jay and Steller’s Jay.

And that’s one of the primary dangers of shoving several totems into one category–you aren’t letting each totem fully express itself. Going back to the not-really-a-totem Black Panther, if you get stuck on the color of melanistic jaguars and leopards and don’t instead look at what makes each species unique, you may as well just make a study of the color black and ignore the animals altogether. If you talked to Jaguar and Leopard as individuals, though, you might find that Jaguar (being a water-loving cat) wants you to focus on being comfortable in multiple settings, not just the ones that are easiest for you, while Leopard (who hates water) may urge you to play to your strengths, as just one example. Or you might find that it’s Jaguar who wants to work with you and keeps showing up in his melanistic form, while Leopard doesn’t have much to offer you.

–It encourages appreciation of biological diversity

Despite our attempts to exterminate massive numbers of species on this planet, Earth is still host to a mind-boggling array of animals, plants, fungi and other living beings. Only a scant few ever make it into totem dictionaries; many have never even been identified by science. By limiting our focus to general categories like “Bear” or “Pine”, we’re losing out on the ability to engage with what makes each species unique and how each contributes to its ecosystem(s).

Let’s look at foxes, for example. There are twenty-four species of fox, yet when most totem dictionaries talk about the totem Fox, they really mean Red Fox in particular. This doesn’t take into account Gray Fox, Swift Fox, and all the other foxes that range across habitats varying from sandy deserts to Arctic tundra, wide forests to tiny islands. I’ve worked with several of the Fox totems, and they’re an incredibly fascinating group. As with Blue Jay and Steller’s Jay, I wouldn’t have been able to appreciate their individual natures if I’d just tried to work with “Fox”.

When we foster a greater appreciation of biological diversity, we often want to protect it. I am constantly amazed every time science discovers a new species, and the many ways in which life manifests are an unending source of joy and wonder for me. But I also know how threatened that diversity is, and so I act to try and protect it as best as I can. When we know exactly what we have to lose, we’re more motivated to keep it safe.

–It can help you connect more deeply to your local bioregion

This doesn’t just go for the diversity of species, either. Species exist in habitats and ecosystems, and living beings interact with landforms, climate and other natural features and forces in interrelated systems. A bioregion is a portion of land that has more or less the same sorts of living beings, geology, weather pattern and other features; it’s often defined by the watershed of the largest river in the area.

Now, it’s okay if you have a totem whose children are native to someplace you’ve never been. But when you work with totems native to your bioregion, there’s more potential both for learning from them and gaining a deeper connection to the land you live on. When I was growing up in Missouri, I was very close to the land; while I didn’t recognize totems per se, their influence was there nonetheless. I moved away after college, and it wasn’t until I moved to Portland that I developed a similarly strong connection to the land. This was facilitated in large part by the totems I worked with, first Steller’s Jay and Scrub Jay, and then an increasingly diverse host including Douglas Fir, Poison Oak, Black Morel, and many others. My totemism ceased to be solely about what sorts of changes I could make in my life and shifted into a more mutually beneficial set of relationships. These days I am an active environmentalist and advocate for nonhuman nature in the Northwest and elsewhere; I also work to reconnect my fellow humans with the rest of nature for the benefit of all involved, and a lot of that is due to my totemic work.

–It’s good practice to get better at totemism

When you rely on a totem dictionary to give you the answers, you’re taking the easy way out. All you have to do is look up the animal, plant or other totem in question, read whatever the author determined was important, and voila–instant gratification! Unfortunately, this really doesn’t prepare you for what happens when you run across a totem that isn’t in any book, or when a known totem starts talking to you about lessons and concepts that aren’t in any of the stereotyped meanings offered by the plethora of dictionaries out there. I’ve lost track of how many times I’ve seen someone ask on a totem-related forum or group “I can’t find anything about Elephant Shrew/Miner’s Lettuce/Black Mold as a totem! Can anyone tell me what it means?” We expect to be spoon-fed enlightenment, and we cheat ourselves dearly in the process.

Working with the totems of individual species helps you break out of that 101 rut. For one thing, you have to be aware that there are several species, not just “Swan” or “Maple”. And you have to research which one you’re talking to. But then you can’t be sure if whatever dictionary entry you happen to find applies to the species-specific totem in question; the information on Crow may apply mostly to the American Crow, but what if your totem is Jungle Crow? You can’t just fall back on a generic “Crow” entry then, not without risking missing a lot of what Jungle Crow has to say. You have to do the work yourself.

And you’ll be better off for it, too. It requires you to be better at communicating directly with the totems, and not just the ones that come easily to you. You’ll figure out how to tell whether a totem is happy or upset to see you (even if it doesn’t say a word to you), or whether it’s even interested in you at all. Over time you’ll develop more ways to work with the totems, from formal rituals to daily practices, and you’ll get better at noticing when a new totem is trying to get your attention (and when it’s just wishful thinking and confirmation bias on your part.) Best of all, you won’t have to go through the process of asking some stranger on the internet “Hey, what does this totem mean?” because you’ll know how to find out for yourself–and that’s empowering.

–What about hybrids and subspecies?

There are plenty of animals that can hybridize with each other, and often do in nature. Blue jays and Steller’s jays largely keep to their own territories, but in a few places where the ranges meet they’ve been known to crossbreed. Horses and donkeys can produce both mules and hinnies (depending on who was the father and who was the mother.) And red wolves may be a long-established hybrid of the gray wolf and the coyote, while the brush wolf is a more recently recognized cross of the two species. Even within a recognized species there may be several subspecies; the Arctic wolf, dingo and domestic dog are all considered subspecies of the gray wolf.

So how do we deal with species-specific totems in these cases? Longevity has a lot to do with it. The red wolf has been a distinct enough being, genetically and phenotypically, that it’s considered its own species, and it has its own totem. While there have been wolf-coyote hybrids since the advent of the red wolf, these have largely been watched over by Gray Wolf and Coyote, and in my experience Brush Wolf has not yet materialized as a unique totem.

Subspecies are generally close enough to each other to not require their own totem; Gray Wolf does watch over eastern timber wolves and Arctic wolves alike. However, sometimes a subspecies takes on enough of a life of its own that a unique totem emerges from its energy; Dingo and Domestic Dog are both examples of cases where wolves were so significantly changed by their relationships with humans and their environment that they diverged widely from “wolf-ness”. The totems Gray Wolf, Dingo and Dog are all very close to this day, and will often work together in rituals and other activities.

Keep in mind, of course, that this is all based on my own experiences, and your mileage may vary. At any rate, I hope I’ve impressed upon you the importance of working with the totem of a species, not a generic group. In my next post I’ll be talking about why totemism isn’t just about animals, why you may wish to work with plant, fungus and other non-animal totems, and the importance of the totemic ecosystem.

A master list of Totemism 201 posts may be found here.

Did you enjoy this post? Please consider purchasing one or more of my books on totemism and related topics! They include more in-depth information on working with totems, to include topics not discussed in this essay series.

Totemism 201: Why Totem Dictionaries May Be Hazardous to Your Spiritual Growth

Those of you who have been following my writing for a while know that I’m biased against totem dictionaries. A totem dictionary is any of a number of books on totems (almost always animal totems) in which the bulk of the text is dedicated to dozens of dictionary-style entries on stereotyped meanings of various totems. The entries are often formatted thusly:

- * The totem’s species (usually a large mammal or bird, less often a reptile, fish or invertebrate)

- * Key words (the Cliff’s Notes version of the totem’s stereotyped meaning)

- * Some random stuff like astrological signs, moon phases or other correspondences that supposedly match up with this totem

- * A few paragraphs on mythology about the animal and what the animal symbolizes in various cultures (usually assorted Native American cultures, or the dreaded “the Native Americans believed…”)

- * A bunch of writing of what the author thinks the totem means and/or whatever meanings they gleaned from other totem dictionaries, all presented as The One True Meaning of this totem

Seems pretty simple, right? All you have to do to get the answers you seek is open up the book to the animal you seek, read about it, and hey presto–you have your answers, all in a neat little package. So what’s wrong with this picture? Well, actually, you can criticize a few things:

–What the book says isn’t what may be

Totems are not one-dimensional characters; nor are they Pokemon. What they are, as far as I’ve been able to discern over the past couple of decades, is archetypal beings that embody the qualities of their given species, as well as the various relationships that species has with others, humans included. They have personalities, often more complex than we give them credit for, and they don’t act the same toward every single person who contacts them. Gray Wolf, for example, is not always “the teacher”, and is not always happy to see everyone who seeks him out. While my relationship with him has been pretty positive (he’s been with my much of my life), I know people that he’s been rather hostile to. And even with me it’s not just a matter of “Yay, this is my totem, he’s going to give me lots of awesome powers and do things for me!” There are times he’s been harsh with me and, quite honestly, times when I’ve had to work with other totems to help un-learn and balance out some of his less favorable traits.

So when someone asks “What does the totem Wolf mean?” and they get a bunch of books and websites giving them a bunch of stereotyped meanings, they’re likely to just stick with those and not go any further. That’s like someone who want to meet you asking a few of your friends and acquaintances for a one-word summary of who you are and then expecting you to only behave according to what you’ve been told. You can see how limiting that is!

I do understand that some people, especially newcomers to totemism, like reading what other people have experienced, especially with less common totems. But that should be only for comparison’s sake, not as holy writ. Otherwise you run the risk of closing yourself off from what a given totem really wants to talk to you about.

–No dictionary can include all totems

There are literally millions of animal species worldwide (not counting the ones we’ve driven extinct), including almost a million insect species alone. Add in all the many thousands of species of plant, fungus, bacteria, archaea, and other living beings out there, and there’s a LOT of biodiversity to take into account. Every single one of those species has a totem. So do all the extinct species that have ever graced this planet. We don’t even know the identity of most of them.

So it’s not at all surprising that you simply cannot fit every single totem into a dictionary. This means, of course, that totem dictionaries (and, by extension, totem divination decks) are severely limited in possibilities. Most of them tend toward what I call the BINABM (Big, Impressive North American Birds and Mammals), like Wolf and Elk and Eagle and Fox and Deer and Hawk and are you sensing a pattern here yet? Note, too, that few of them talk about the totems of individual species; every snake totem from North Pacific Rattlesnake to Reticulated Python ends up smushed into the general category of “Snake”, and “Spider” somehow is supposed to stand in for a diversity of arachnids ranging from Black Widow to the many sorts of Assassin Spider to the plethora of Tarantulas running around without woven webs. That’s akin to someone saying “Well, your last name is Smith and so that must mean you’re exactly like every other Smith out there, oh, and do you do blacksmithing because I really need a ritual knife made for our coven’s next sabbat.”

The totem dictionary discourages people from exploring outside of this slender, and rather inaccurate, set of definitions it sets out. Some of them admittedly do give you a few exercises to do with your totem, even if it’s not one that’s listed in the book. But I really think these authors would do better to spend more time giving people more material for working with their totems, rather than padding out the page count with dozens of dictionary entries.

As for the issue with not exploring the totems of individual species? I’ll be covering that in more depth in a separate post later on, so I’ll table it for the moment. (Just hold your horses–including Domestic Horse, and Przewalski’s Horse, and Grevy’s Zebra…)

–The dictionary format encourages intellectual laziness and spiritual selfishness

From what I’ve observed over the years, people who seek out totem dictionaries online or in books are usually looking for easy answers. They want someone to tell them “Well, Deer is the keeper of psychic powers, and Rabbit teaches gentleness, and Raven is the darkness in everyone’s soul” and so forth. And then once they’ve identified that tidbit of information, that’s as far as a lot of them go with the relationship. They look in their own lives for places where they can increase their intuition, or become gentler, or, uh, unleash a tide of darkness and woe upon their enemies. And now that they’ve found “their” totem, they may buy a bunch of books and t-shirts and cheaply-made-in-China statues of that being. But they don’t often take the totemic relationship any farther than that. Where’s the curiosity? Where’s the desire to learn more about the totem beyond what some book tells them? Where’s the reward in doing the work yourself? Vanished in a haze of instant gratification.

This is not to say that I am the only totemist who goes into more detail with my work than “Oh, here, read this book.” I know a good number of them, in part because I’ve tried to seek out folks of a like mind over the years and been generously rewarded for my efforts. But we’re still a minority amid the fast-food-spirituality crowd. And to an extent, while I am being rather harsh with the basics, I do admit that more advanced practice isn’t for everyone. Some people are content just knowing they aren’t alone. But when that’s all that’s presented to people, it gets a bit frustrating after a while.

Moreover, when someone asks “What does this totem mean?”, do you know what I hear? “What can this totem do for me?” And that’s the general theme of the overwhelming majority of totem dictionaries out there. Upon doing a casual search for books on “animal totems” and “spirit animals” on Amazon, some of the most common words that come up are “power”* and “messages”, both as bonuses you’re supposed to receive from your super-spiffy totem animal who will fix all your problems for you.

Spirituality is not just about “gimme gimme gimme.” Ideally it’s a set of relationships and connections that go both ways. We are not the totems’ biggest priority; they don’t exist primarily to endow us human apes with mystical wisdom and enlightenment. Their biggest concern is taking care of their own physical counterparts, and because humanity is currently waging war on the environment, by necessity they have to interact with us in an attempt to get us to stop killing everything. It’s not to say that some of them don’t genuinely enjoy working with us, to include in personal growth. But we kid ourselves when we talk about how we’re the golden children of the planet and everything revolves around our bipedal asses.

I can only really speak for myself, but as my relationships with various totems have deepened over the years, I haven’t found myself wanting to get even more stuff from them. Instead, the point at which I consider myself to have left basic totemism behind was the point when I began to be motivated by the desire to give back to them. Now, this isn’t in the manner of supplication and “Please don’t kill me” and “Well, I’m making offerings because my ancestors made offerings and that’s what I’m supposed to do, too.” No, I’m talking about caring so deeply for these beings and their physical children that I wanted to make things better for them, even if only a little. It’s like falling deeply in love with someone; you cease to only be attracted to their surface traits, and you instead genuinely want to make their life better as a whole person, joys and flaws and all.

It doesn’t mean I never ask for help, especially in tough times. But I’ve long since left behind the desire to “access power” through my totems; a more accurate phrase might be “connect with” or “create relationship with.”

One final note: you may have noticed that I’ve written some profiles of various totems here and for my Patreon patrons. These are NOT meant to be holy writ! I write them from a personal perspective because my readers tend to like seeing examples of the concepts I write about in action, and it can help illustrate totemic work a little better. But they’re always phrased as “My work with X totem is this”, not “if X totem comes into your life it means this.”

Alright, that’s it for now. In the next post I’ll go into more detail about why it’s important to know the species of the totem you’re working with. And in a later post I will talk about how you can connect with and learn more about a totem without relying on dictionary entries, so stay tuned!

A master list of Totemism 201 posts may be found here.

Did you enjoy this post? Please consider purchasing one or more of my books on totemism and related topics! They include more in-depth information on working with totems, to include topics not discussed in this essay series.

* I recognize that “power animal” is a specific concept in and of itself, and I’m not including that use of the term in this complaint. Rather, I’m talking about phrases like “access the POWER of your totem animal!” and “POWERFUL magic of totems!”, indicating that you, too, can access power by buying this book.

Totemism 201: Totems Are Not Pokémon

I’d like to start the meat of this essay series by criticizing a few of the limitations of non-indigenous totemism as it’s commonly practiced. And I’d like to start with the idea that everyone has a set number of totems, and that’s that.

In years of reading of other people’s work on totems, I frequently come across the idea that everyone has a set number of totems. Some say each of us has only one, and that one totem stays with us for life. Others claims we have two, one for each of our halves (as though we are composed of nothing but dichotomies.) Or they say we have four for each of the cardinal directions, or add in another for center. Countless people are convinced that “the Native Americans”* teach that everyone has nine totems thanks to Jamie Sams’ and David Carson’s book and deck set, The Medicine Cards.

I know exactly where it comes from, too: the insistence on some neat round number that signifies “Okay, you’ve finished the work, now you can relax and bask in the glory of your spiritual development!” I’ve seen people get so caught up in trying to figure out what the “missing” three or four totems in their set of nine are that they don’t actually work with the ones they’ve already identified. Moreover, if they reach that magic number nine (or four, or whatever), if yet another totem makes contact with them then they get all confounded and wonder whether they misidentified one of their totemic dream team.

Folks, this ain’t Pokémon, and you don’t have to catch ’em all. You aren’t prevented from progressing to the next level of your spiritual path if you don’t have a complete set. And you don’t need to look up your totem’s stats in a spiritual Pokédex (a.k.a. the Dread Totem Dictionary, which I’ll skewer in my next essay) before you start to work with them.

The Pokémon approach (“I must have X number of totems!”) is troublesome for a couple of reasons:

–It’s about making totems fit your preconceived map of correspondences and meanings, rather than letting those relationships develop organically. It’s easy to get caught up in trying to shove them into pigeonholes labeled things like “North” and “South” or “left side” and “right side.” This is especially pernicious because the sorts of non-indigenous authors and teachers who perpetuate this sort of pigeonholing apply specific definitions to each category. Picking on The Medicine Cards again, Sams and Carson say that the right side animal “protects your male side” and “your courage and warrior spirit”, while the left side totem “is the protectors of your female side” and teaches you about “relationships and mothering.” Not only is this incredibly sexist and heterocentric, but what if the totem you get for your left side in your super-spiffy card reading is Loggerhead Sea Turtle, who buries her eggs in the sand and then abandons the babies to their fates while she returns to the ocean to live a largely solitary life? Moreover, what if what she wants to teach you has absolutely nothing to do with relationships and mothering, and everything to do with, say, physical endurance and longevity? I suppose if you engaged your human pattern-recognition skills long enough you could make some connection there–but why bother trying to make Loggerhead fit into that tiny little definition when she could be teaching you the wisdom in learning how to swim, figuratively and literally (or whatever she feels like showing you?)

–It stays at the surface of things and entangles you in minutiae rather than allowing a more organic exploration of a deepening relationship with a totem. Like the totem dictionary, the Pokémon approach to totemism feeds you a bunch of structures you’re supposed to plug your totems into. You’re not really told what to do when things deviate outside of that neat but narrow little worldview. Sure, you can likely figure it out on your own, but there’s a surprising number of people who adhere to the stuff in these books as though they’re holy writ. Some of this is probably a result of many pagans, New Agers and the like having come from the sorts of religions that hand you a pile of dogma that outlines what you’re supposed to believe, think and do. While people in these religions can certainly have deep, meaningful relationships with their own Powers That Be, there are plenty of fundamentalists who stick to the letter rather than the spirit. And that same desire to have all the answers laid out nice and easy carries over into some totemists as well.

Now, since I don’t like to complain without offering at least one solution, allow me to offer up a workable alternative. And it starts with one very simple concept:

There is no single universal number of totems you’re supposed to have, and no universal structure with which to organize them.

Ditch that idea. Toss it out. Right now. Because when you do, you leave yourself available to whatever totems are willing and able to work with you over the course of the rest of your lifetime, whether that’s one or one hundred or any other number. Now you’re able to let them come to you at their own pace, and you can have your initial conversations with them without worrying whether they fit in the proper slot. It’s a very liberating feeling as far as I’m concerned.

How do you view your totems now that you no longer have a scaffolding to hang them in? Well, think of how you treat your friends. You likely don’t think in terms of “Bob is the friend I go to supper with every Thursday night, and Sally is the friend I go hiking with on Sundays, and when I want to go shopping I call Erica” and so forth. No, you let them be individuals and you appreciate them as such. You connect with them for different reasons, but you see them as whole people. And that’s a good way to approach your totems. Not all of them will be buddy-buddy with you, either; some of them might be quite aloof or even borderline hostile. But at least you can let those personalities and relationships grow at their own rate, and appreciate each totem on its own merits rather than whether it fits into your preconceived worldview. And you can decide what your end of the relationship will be like; if you have a totem you’re less comfortable with you can maintain a safe distance until you get more of a sense of why they showed up.

One more really important benefit: you’re able to see how the totems interact with each other. Because you’re not all caught up in “Wait, does Pigeon really fit the qualities of East?” you’re more likely to notice things like how Pigeon responds whenever you call on him and Common Raven in the same ritual. And if one totem introduces you to another, you can pay more attention to how they work together because you’re not busy figuring out where in your structure this newcomer fits. This sort of observation may very well lead to you being able to coordinate your work with several totems at once, combining efforts to achieve a common goal, allowing each participant to contribute as they see fit.

In the next essay, we’ll shake off more preconceived notions by picking apart the totem dictionary.

A master list of Totemism 201 posts may be found here.

Did you enjoy this post? Please consider purchasing one or more of my books on totemism and related topics! They include more in-depth information on working with totems, to include topics not discussed in this essay series.

* Any time someone says “the Native Americans believed…” look askance at them. “Native Americans” comprise thousands of individual cultures throughout the Americas, each of which has their own set of ever-evolving cultural and spiritual traditions, not all of which include totemism. Like many non-indigenous writers, Sams and Carson have nabbed little bits of lore and practice from an assortment of indigenous cultures, mish-mashed them together with New Age frippery like the lost continent Mu (from whence all the Native cultures supposedly originated), and then call it genuine Native American spirituality. Moreover, despite five hundred years of genocide, many Native American cultures still exist today, and it’s more accurate to say members of a given culture “believe” something rather than “believed.”

Totemism 201: An Introduction and Purpose (And Master List of Totemism 201 Posts)

As of this upcoming spring it will be nineteen years since I became pagan and began working with totems, among other spiritual beings. While my path has wended its way through a variety of areas of study and practice, the totems have been a constant presence throughout. While my initial work was exclusively with animal totems, since moving to Portland in 2007 I’ve expanded my work to include the totems of plants, fungi, landforms, and other manifestations of nature. From the beginning my relationships with the totems have been influenced by my status as a non-indigenous person trying to bond with the land I found myself on. I’ve been inspired by others authors’ writings on the subject, both historical and contemporary, but rather than following traditions from other cultures I have primarily worked with the totems to create my own path.

Unlike a fair number of non-indigenous practitioners, I’ve taken these relationships far beyond the basic “This totem has this meaning” level. While I’m far from the only advanced neopagan totemist out there, I’d like to see more people move their practices past stereotyped meanings and begging totems for help. I recognize I’m somewhat in the minority in this regard. Most folks who pick up a book or hunt for a website on totemism are just looking for quick and easy answers like “What does the (totem) Fox say?” and “What sort of spiritual message am I getting when a highly territorial bird like a red-tailed hawk keeps showing up in my yard, using the nearby telephone pole as a perch to hunt for delicious, delicious rodents?” I prefer writing about more complex ways of relating to these spirit beings of nature, and insist that my readers do the work themselves, even if it takes years. While I have a growing audience of folks who agree, I’m not very likely to topple Ted Andrews and his eternally-loved Animal-Speak* for “most popular totemism book ever.”

So why do I feel it’s so important to grow one’s totemic practice when so many insist on buying into an easy-answers format? Well, for one thing there’s a lot more to learn from an individual totem than whatever blurb that’s passed around from one totem dictionary to the next. Just like any other relationship, your connection with a totem grows and evolves over time, and what they have to show you may expand far beyond what you read in such and such book; Gray Wolf may say nothing whatsoever about being a teacher, and Red-tailed Hawk may never mention being a messenger, and so forth. It’s crucial to cultivate an open mind; I’ve lost track of how many people I’ve seen posting in forums about how a totem tried to teach them something that wasn’t in the book, and rather than simply going with it they worried they were doing something wrong. I find that rather sad; when faced with such a situation I prefer to promote a sense of enthusiastic exploration over one of self-doubt.

More importantly, the common totemic paradigm is incredibly selfish. Look at almost any book or website on animal totems (or spirit animals, etc.) and the emphasis is on what you can get from these beings, how they resonate with you, how they can enhance your life, and so forth. As far as I’m concerned, one of the first steps to becoming a more advanced totemic practitioner is the realization that it’s not about you, and that you (and humanity in general) are only a very tiny portion of the grand scheme of things. Beyond that it’s imperative to look at what you can give back to the totems, their physical counterparts and the habitats they live in. The New Age emphasis on non-indigenous totemism keeps saying “take, take, take, take!”; my own practice has grown to encompass “give, give, give, give!” more and more as the years have passed by. The balance of give and take may shift over time; sometimes I need to rely more heavily on my totems than others. But I have long since given up the solely “What’s in it for me?” approach so popular with the dictionary style of totemism.

I’d like to see that trend spread. Each totem is the guardian of its own species; they’re concerned with far more than us, something we all too often ignore in our quest for personal enlightenment. We humans already take so much from the rest of the beings on this planet, and we insist on taking a lot from their totems without giving back to them. I want to foster an approach to totemism that nurtures a sense of responsibility toward the totems and their children rather than this “I want all the answers and I want them now!” approach that’s so popular.

When I wrote my first book, Fang and Fur, Blood and Bone, almost a decade ago, I wrote it because I was tired of totem dictionaries and wanted there to be more on totemism and animal magic than easy answers. My books and other writings have continued in that tradition, and you can consider this essay series the newest iteration thereof. You won’t find pre-scripted rituals here, and certainly not dictionary entries of what totems supposedly mean universally; I’m also not going to go into introductory material like how to find totems. It’s not an exhaustive how-to resource; that would be counter to its very intent. In part it’s a collection of essays punching holes in some (figurative) sacred cows of neopagan totemism. These writings are also meant to offer several potential starting points for expanding and growing your own practice in the directions you and your totems deem best. Let go of the idea that you have to grow your practice in a linear manner; instead, let it grow organically, and use the essays I write as seeds for that endeavor.

Master List of Totemism 201 Posts:

Totemism 201: Totems Are Not Pokémon

Totemism 201: Why Totem Dictionaries May Be Hazardous To Your Spiritual Growth

Totemism 201: Why Species Are Important

Totemism 201: It’s Not Just About the Animals

Totemism 201: It’s Not Just About Us, Either

Totemism 201: Why Going Outside is Important

Did you enjoy this post? Please consider purchasing one or more of my books on totemism and related topics! They include more in-depth information on working with totems, to include topics not discussed in this essay series.

* No offense to the late Mr. Andrews; his book was admittedly my first book on the topic, and while much of it is the sort of dictionary I don’t care for, he did include a lot of useful exercises for bonding more deeply with one’s totems, and my signed copy that I’ve been toting around for almost twenty years is one of my prized possessions on my bookshelf.

A Naturalist Pagan Approach to Gratitude

Supposedly Thanksgiving is about gratitude, a rather pagan-friendly appreciation of the harvest that will help us get through the hard winter ahead. In my experience, it’s primarily been a time to get together with family and/or friends, eat lots of food (and for some people get tipsy or drunk on whatever booze is available), and not have to go to work. Other than a prayer before the meal, I’ve observed very little overt gratitude being given amid the festivities. It’s not that I don’t appreciate the value of time with good people and plenty to eat, and I definitely disapprove of the growing trend of nonessential personnel having to work on Thanksgiving proper. But the original meaning of the holiday seems to have been rather lost in practice.

Perhaps this is in part because deliberate harvest festivals have been a part of my spirituality for the better part of two decades. Because I came to paganism after being raised Catholic, and I didn’t have a coven or other group to indoctrinate me formally with a predetermined set of spiritual parameters, I had to really consider what beliefs and practices I was adhering to and why. So I learned about the three harvest Sabbats–Lammas, Fall Equinox, and Samhain–and their historical counterparts in various European cultures. As I spent more time gardening, I was able to put theoretical practices to the test, exercising a new layer of gratitude as I watched seeds I planted sprout, grow, and come to fruition. The older I got and the more my path developed, the less I took my spirituality for granted.

These days, gratitude is deeply ingrained in my path because I know too much now to sustain ignorance. My roots are firmly embedded in urban sustainability and environmental awareness, and so I am acutely aware of where my food comes from and the cost it exacts on the land. “Harvest” isn’t just something to be celebrated in autumn; I’m able to get all sorts of food year-round, and that means there’s a harvest going on somewhere every day. As much as I try to stay local and seasonal, it’s not always within my budget (financial or temporal), and so I sometimes find myself buying out of season produce flown in from far away and processed foods whose ingredients were harvested weeks ago, moreso in the winter.

This means that each meal is infused with awareness and appreciation for the origins of each of the ingredients, whether I grew them myself or not. I can’t help but be grateful to those who made sure I was able to eat, whether that’s the animals, plants and fungi that died (or were at least trimmed back) to feed me, or the people who took care of them throughout their lives, or those who harvested and prepared them. I also have gratitude for the land that supported the food as it grew, particularly those places where chemical pesticides, fertilizers and other “enhancements” have destroyed the health of the soil. And I think, too, of the air, water, and land polluted by the fossil fuels used to grow, process and transport the food to me, and the other wastes that result from the sometimes convoluted path from farm to table.

All of this is summed up in a short prayer I’ve said before meals–quietly or out loud–for many years:

Thank you to all those who have given of themselves to feed me, whether directly or indirectly.

May I learn to be as generous as you.

Notice there’s two parts to that prayer–the acknowledgement of what others have given to me, and a hope that I can be as giving myself. Considering how much some beings sacrifice in order for me to eat, it’s impossible for me to give back exactly as much, at least until I die and my body is buried in the ground to be recycled into nutrients for others. But I can try to give back through more sustainable food choices, and attending to the tiny patch of land in my community garden, and donating food to charity. I can support efforts to gain better rights and working conditions for the migrant workers who pick the produce I eat and the underpaid employees of food processing plants. I can work to educate others about the problems inherent in our food systems and what we can do about them. All these are a far cry from being as generous as a being that died to feed me, but they’re a start.

My gratitude drives me to do what I can each day, not only to appreciate what I’m given but to care for those who have given it to me. The more I know about where my food comes from, the more driven I am to be a responsible part of this unimaginably large network of supply and demand, resource and consumption. Being grateful isn’t just about taking things with a “Yes, thank you”. It’s also the desire to give back, to demonstrate appreciation. The prayer at the beginning of the meal is only the barest glimmer of that urge, and it means little if it’s not followed up by action.

And so this Thanksgiving, as I am surrounded by others and as we prepare to eat turkey and stuffing and green beans and the canned cranberry sauce that retains its cylindrical shape all by itself, it’ll just be another day in which I am grateful and in which I try to enact as well as voice that gratitude. It’s also a good day to renew my commitment to that thankfulness and all it entails, in thought and deed alike. I may never achieve perfection; there are always more thanks to be given. But let this time of year be the rejuvenation of my efforts nonetheless.