I’d like to start the meat of this essay series by criticizing a few of the limitations of non-indigenous totemism as it’s commonly practiced. And I’d like to start with the idea that everyone has a set number of totems, and that’s that.

In years of reading of other people’s work on totems, I frequently come across the idea that everyone has a set number of totems. Some say each of us has only one, and that one totem stays with us for life. Others claims we have two, one for each of our halves (as though we are composed of nothing but dichotomies.) Or they say we have four for each of the cardinal directions, or add in another for center. Countless people are convinced that “the Native Americans”* teach that everyone has nine totems thanks to Jamie Sams’ and David Carson’s book and deck set, The Medicine Cards.

I know exactly where it comes from, too: the insistence on some neat round number that signifies “Okay, you’ve finished the work, now you can relax and bask in the glory of your spiritual development!” I’ve seen people get so caught up in trying to figure out what the “missing” three or four totems in their set of nine are that they don’t actually work with the ones they’ve already identified. Moreover, if they reach that magic number nine (or four, or whatever), if yet another totem makes contact with them then they get all confounded and wonder whether they misidentified one of their totemic dream team.

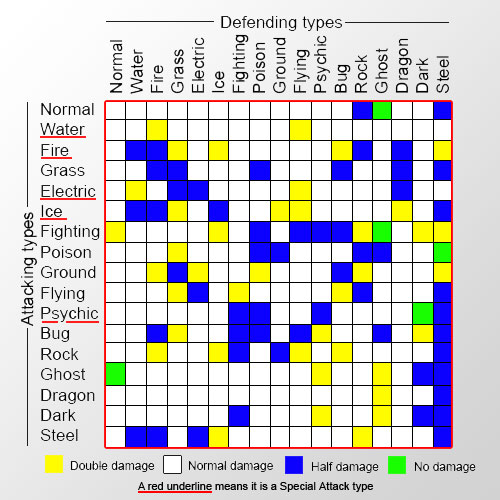

Folks, this ain’t Pokémon, and you don’t have to catch ’em all. You aren’t prevented from progressing to the next level of your spiritual path if you don’t have a complete set. And you don’t need to look up your totem’s stats in a spiritual Pokédex (a.k.a. the Dread Totem Dictionary, which I’ll skewer in my next essay) before you start to work with them.

The Pokémon approach (“I must have X number of totems!”) is troublesome for a couple of reasons:

–It’s about making totems fit your preconceived map of correspondences and meanings, rather than letting those relationships develop organically. It’s easy to get caught up in trying to shove them into pigeonholes labeled things like “North” and “South” or “left side” and “right side.” This is especially pernicious because the sorts of non-indigenous authors and teachers who perpetuate this sort of pigeonholing apply specific definitions to each category. Picking on The Medicine Cards again, Sams and Carson say that the right side animal “protects your male side” and “your courage and warrior spirit”, while the left side totem “is the protectors of your female side” and teaches you about “relationships and mothering.” Not only is this incredibly sexist and heterocentric, but what if the totem you get for your left side in your super-spiffy card reading is Loggerhead Sea Turtle, who buries her eggs in the sand and then abandons the babies to their fates while she returns to the ocean to live a largely solitary life? Moreover, what if what she wants to teach you has absolutely nothing to do with relationships and mothering, and everything to do with, say, physical endurance and longevity? I suppose if you engaged your human pattern-recognition skills long enough you could make some connection there–but why bother trying to make Loggerhead fit into that tiny little definition when she could be teaching you the wisdom in learning how to swim, figuratively and literally (or whatever she feels like showing you?)

–It stays at the surface of things and entangles you in minutiae rather than allowing a more organic exploration of a deepening relationship with a totem. Like the totem dictionary, the Pokémon approach to totemism feeds you a bunch of structures you’re supposed to plug your totems into. You’re not really told what to do when things deviate outside of that neat but narrow little worldview. Sure, you can likely figure it out on your own, but there’s a surprising number of people who adhere to the stuff in these books as though they’re holy writ. Some of this is probably a result of many pagans, New Agers and the like having come from the sorts of religions that hand you a pile of dogma that outlines what you’re supposed to believe, think and do. While people in these religions can certainly have deep, meaningful relationships with their own Powers That Be, there are plenty of fundamentalists who stick to the letter rather than the spirit. And that same desire to have all the answers laid out nice and easy carries over into some totemists as well.

Now, since I don’t like to complain without offering at least one solution, allow me to offer up a workable alternative. And it starts with one very simple concept:

There is no single universal number of totems you’re supposed to have, and no universal structure with which to organize them.

Ditch that idea. Toss it out. Right now. Because when you do, you leave yourself available to whatever totems are willing and able to work with you over the course of the rest of your lifetime, whether that’s one or one hundred or any other number. Now you’re able to let them come to you at their own pace, and you can have your initial conversations with them without worrying whether they fit in the proper slot. It’s a very liberating feeling as far as I’m concerned.

How do you view your totems now that you no longer have a scaffolding to hang them in? Well, think of how you treat your friends. You likely don’t think in terms of “Bob is the friend I go to supper with every Thursday night, and Sally is the friend I go hiking with on Sundays, and when I want to go shopping I call Erica” and so forth. No, you let them be individuals and you appreciate them as such. You connect with them for different reasons, but you see them as whole people. And that’s a good way to approach your totems. Not all of them will be buddy-buddy with you, either; some of them might be quite aloof or even borderline hostile. But at least you can let those personalities and relationships grow at their own rate, and appreciate each totem on its own merits rather than whether it fits into your preconceived worldview. And you can decide what your end of the relationship will be like; if you have a totem you’re less comfortable with you can maintain a safe distance until you get more of a sense of why they showed up.

One more really important benefit: you’re able to see how the totems interact with each other. Because you’re not all caught up in “Wait, does Pigeon really fit the qualities of East?” you’re more likely to notice things like how Pigeon responds whenever you call on him and Common Raven in the same ritual. And if one totem introduces you to another, you can pay more attention to how they work together because you’re not busy figuring out where in your structure this newcomer fits. This sort of observation may very well lead to you being able to coordinate your work with several totems at once, combining efforts to achieve a common goal, allowing each participant to contribute as they see fit.

In the next essay, we’ll shake off more preconceived notions by picking apart the totem dictionary.

A master list of Totemism 201 posts may be found here.

Did you enjoy this post? Please consider purchasing one or more of my books on totemism and related topics! They include more in-depth information on working with totems, to include topics not discussed in this essay series.

* Any time someone says “the Native Americans believed…” look askance at them. “Native Americans” comprise thousands of individual cultures throughout the Americas, each of which has their own set of ever-evolving cultural and spiritual traditions, not all of which include totemism. Like many non-indigenous writers, Sams and Carson have nabbed little bits of lore and practice from an assortment of indigenous cultures, mish-mashed them together with New Age frippery like the lost continent Mu (from whence all the Native cultures supposedly originated), and then call it genuine Native American spirituality. Moreover, despite five hundred years of genocide, many Native American cultures still exist today, and it’s more accurate to say members of a given culture “believe” something rather than “believed.”