So I had a special request from one of my Patrons over on Patreon. They wanted to get some advice on storing art supplies, which sounds simpler than it actually is. See, if you’re an artist, you probably have a tendency to buy way more supplies than you actually need in the moment, often spurred on by creative impulses that say “Hey, look at this neat thing–you could TOTALLY make something out of it!” Which is how, over the years, I have ended up with everything from a vintage floorstanding radio to a full-sized taxidermy hyena to way more tchotchke shelves than anyone has any business owning.

Having been a hide and bone artist for two decades has at least given me the opportunity to figure out how to best store lots of big, bulky supplies like fur coats and antlers. Now, I am not one of those people who has an entire basement floor to work with, with walls full of shelves holding a hundred identical plastic tubs, each neatly labeled in legible handwriting. You won’t see my studio in a magazine extolling “Twenty Enviable Artists’ Spaces.” But I’ve made do with a whole bunch of living situations for me and my stuff.

The first thing you need to think about when stashing your art supplies is the space you have to work with. My living quarters have ranged from a single bedroom to a spacious two bedroom apartment. Storage has been everything from tiny closets to the laundry room. These days my current studio includes not only part of a house but a loft in a barn for storage as well. (I am incredibly spoiled, believe you me.)

You’re going to have to be realistic about the space available to you, especially if you live with other people. It’s tempting to just let it all hang out, so to speak, but that’s not really fair to anyone besides you in your creative moments. So assess what space you can reasonably have for your supplies. It’s best to focus on out of the way spots like closets, shelves, and back rooms that don’t get that much traffic. This isn’t just to keep things out of the way, but also because these spaces are good for keeping things more or less contained.

Next, you need things to keep things in. I am a big fan of plastic bins and milk crates. They’re boxy, easy to stack and easy to move around, and are often abundant in thrift stores. I mean, if you really need all your bins to match you can go to any general-stuff store and pick up a bunch of the same type, but I have poached mine from all sorts of sources, even free piles on the side of the road after someone has moved. They’re mismatched, but they work pretty well.

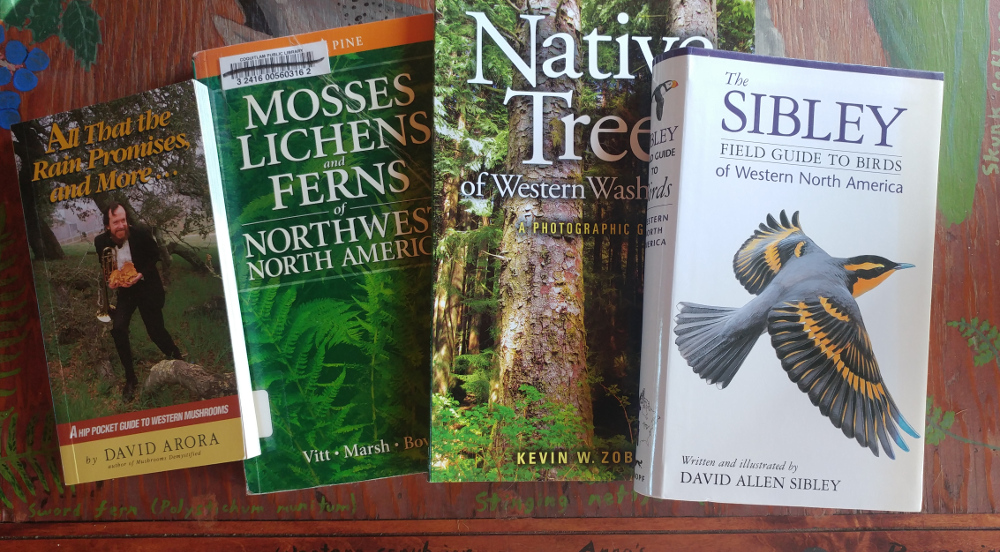

Soft, squishy things lend themselves well to being stuffed in bins, like the ones in the picture at the beginning of this post. Most of mine are full of fur and leather scraps of varying sizes and sorts. I also have a few that are full of assorted smaller odds and ends, like shells and feathers and so forth. Keep in mind that the bigger the bin the more stuff you can fit, but the more you also have to sort through to find that one tiny thing that inevitably has fallen to the very bottom. You can also put hard, awkward things like antlers and bones in bins, though you may have to play a little Tetris to get them to fit right.

Crates work well for smaller hard, awkward things. However, my favorite use for them is as storage for stacks of jewelry organizing boxes. These are those shallow tray-like boxes with little dividers in them that are perfect for beads, fishing lures, hardware, and other teeny little easily-lost items. One milk crate will typically hold a stack of five, and then you can stuff some baggies of other stuff in along the side. Make sure that you don’t put things in above the top edge, or else they won’t stack properly. I use the very top crate in a stack for stuff that won’t fit neatly and might stick out the top. I don’t like to stack more than four crates up as they can get tipsy otherwise. (Plus it’s a pain having to unstack and restack them every time you want something from the bottom crate–which is a great reason to put the things you use the most in a crate higher up the stack.)

Not everything is perfectly neat, of course. I also have a shelving unit full of oddly-shaped cardboard boxes, and stacks of more boxes, and bags of packing materials, and so forth. But I make everything more or less fit, and since a lot of that stuff is either packing materials or destashed art supplies just waiting for someone to buy them, most of what’s there is temporary. (Don’t feel bad if you can’t make everything you have fit into neat boxes, so long as you can keep it basically contained.)

I also am fortunate enough to have a decent work bench. I have some small benchtop shelves for things I use a fair amount like adhesives and tools. The rest of the bench….well…the condition of that depends on how busy I’ve been. But having a flat surface that is reserved for my work helps keep it somewhat contained. If you can have a table that isn’t shared with other things (like, you know, meals) make the best use of it you can. Otherwise, put your stuff away as soon as you’re done working so that you stay in the habit of keeping things neat.

One more thing: it’s really important to reorganize and declutter on a regular basis; you can either sell or donate whatever you cull. If you watch the supplies section of my Etsy shop, you’ll notice that I destash stuff several times a year. That’s just the stuff that I think my customer base may be interested in. I donate even more than that every year to SCRAP, a Portland-based nonprofit that resells art supplies and uses the money in art education and other community projects. Not only does this help me make space for more art supplies (or, you know, things that aren’t art supplies) but it also lets me revisit what I already have in hand. One of my biggest challenges when sorting is not getting distracted by “Ooooh, a shiny thing…let me just stop a minute and start making it into something.” Usually the workbench ends up with a pile of projects-to-be by the time I’m done sorting and reorganizing.

Of course, this is just the art supplies. My personal animal skull collection, on the other hand, isn’t so neatly contained. But that’s another post someday…

Did you enjoy this post? Consider becoming my Patron on Patreon at http://www.patreon.com/lupagreenwolf for as little as $1/month!