Over the years, my spirituality has shifted in the nature of its practice. For a long time I was a dedicated ritualist. I spent hours before my altar, altering my state of consciousness through chants and dance, and working myself into an endorphin-fueled high that helped me to break out of my own headspace. It was during those times that I felt most at one with the rest of the world, or at least some portion of it not bounded by my own skin. I had some pretty incredible experiences, and on occasion I’ll still indulge in more elaborate practices when the situation calls for it.

More recently I’ve become dissatisfied with ritual as my primary vehicle of connection. It can be time-consuming, it isn’t always practical, and it sometimes leaves the ordinary parts of life looking–well–ordinary. As the animal totems I’ve worked with have urged me deeper into their ecosystem, engaging with the totems of plants, fungi, waterways and others, it’s given me cause to rethink my approach to the world around me. The more I understood about the interconnectedness of ecosystems, the less I felt I had to put myself into a special place and time to feel I was a part of something greater.

And so these days I quite easily slip into that sense of unity with the universe. I touch a leaf, or pick up a stone, or gaze at the wide blue skies over the Oregon sagebrush desert, and I know in that moment that I am anything but alone, isolated and detached. It is only human hubris that led me to believe anything else, the Catholic upbringing and consumerist setting that both told me “You are more than an animal; you are something special; you deserve to take whatever you want from nature”. That elevated status may sound like a place of power, but in reality the pedestal can be an incredibly isolating place to be.

What I understand now is that every living thing is my relative. Every piece of substance on this earth shares something in common with me, be it life, or elements, or merely the fact we are composed of atoms. There is nothing on this planet, nothing in this universe, that is truly alien to me. I am a part of a larger community; I always have been. Every being that has come before is my ancestor. I watched a video of David Attenborough examining the forelimb of a fossil of Tiktaalik, one of the first amphibians to walk on land. He pointed out how, like humans, this 375 million year old creature had a humerus, a radius and ulna, and a constellation of wrist bones. Even if Tiktaalik isn’t a direct ancestor by genes, it is of my family nonetheless.

What I understand now is that every living thing is my relative. Every piece of substance on this earth shares something in common with me, be it life, or elements, or merely the fact we are composed of atoms. There is nothing on this planet, nothing in this universe, that is truly alien to me. I am a part of a larger community; I always have been. Every being that has come before is my ancestor. I watched a video of David Attenborough examining the forelimb of a fossil of Tiktaalik, one of the first amphibians to walk on land. He pointed out how, like humans, this 375 million year old creature had a humerus, a radius and ulna, and a constellation of wrist bones. Even if Tiktaalik isn’t a direct ancestor by genes, it is of my family nonetheless.

Do you know what one of my favorite things to ponder is? Consider the trillions of cells that make up a human body. These cells are the direct descendants of independent, unicellular life forms that, billions of years ago, joined together and worked in harmony in order to meet the challenges life threw at them. This may have happened independently as many as four dozen times throughout the history of this planet, and each multicellular revolution resulted in a different sort of being. One begat the line that would become animals.

So we are really composed of trillions of tiny lives. They’re each so specialized and enmeshed as to be utterly dependent on the entire organism, and die without its support. We think of ourselves as more hardy than that–but don’t we, too, ultimately die without an ecosystem to support us? We just take longer to expire than a few skin cells scraped off on a jagged branch on the trail.

We don’t have definitive proof that the planet is a living organism in the sense we think of it, nor the galaxy, nor the universe. But we can take a certain symbolic, poetic stance in that regard. And I think it’s a valuable shift in mindset that melds romance and science. Not that science is without romance of its own. Most scientists are not cold, 100% rational people; they have emotions and biases, too. And many scientists I’ve met have been ridiculously passionate about the parts of the world that fascinate them–if not everything that exists, starting with their own specialty.

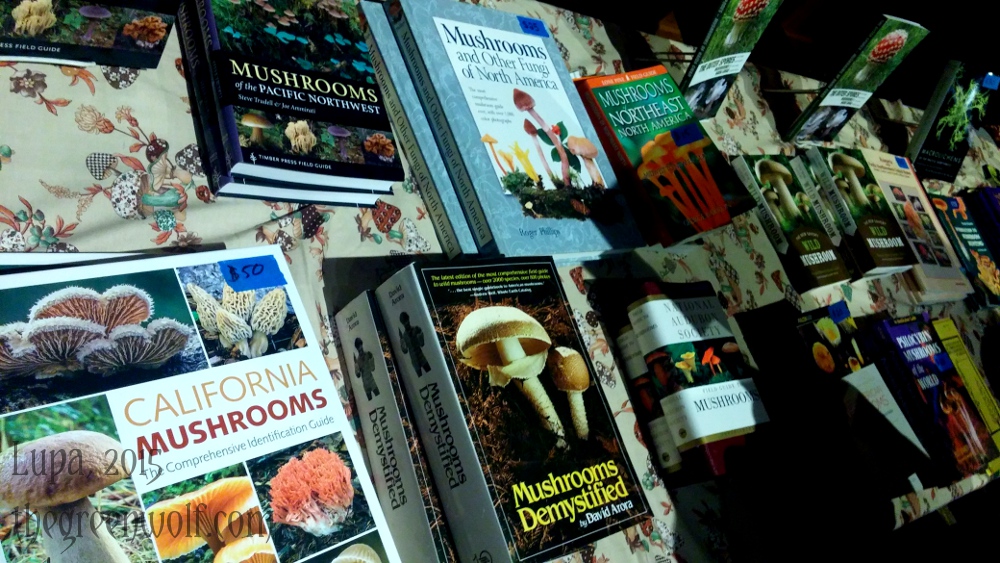

Science is not the enemy just because it says there is no clear evidence of planet-as-organism. Science is a lens onto the mind-staggering intricacy we have found ourselves in the moment we are born into this world. If it does not indulge in speculation beyond ideas to be tested, that doesn’t make it lacking in imagination or wonder. Those who say there is no magic here because life isn’t like a fantasy novel haven’t been paying attention to the unfolding story of the world that the sciences are uncovering. Read enough books, watch enough documentaries, walk out into the world enough times and observe with curiosity, and you too will likely see things that are magical without being supernatural.

Science is not the enemy just because it says there is no clear evidence of planet-as-organism. Science is a lens onto the mind-staggering intricacy we have found ourselves in the moment we are born into this world. If it does not indulge in speculation beyond ideas to be tested, that doesn’t make it lacking in imagination or wonder. Those who say there is no magic here because life isn’t like a fantasy novel haven’t been paying attention to the unfolding story of the world that the sciences are uncovering. Read enough books, watch enough documentaries, walk out into the world enough times and observe with curiosity, and you too will likely see things that are magical without being supernatural.

And really, life itself is the grandest immersive experience any of us will ever get. If I only considered the moments most soaked in endorphins to be where I was truly alive, think of how much I’d be missing out on! I got tired of chasing that connected feeling in fleeting moments of euphoria, and instead decided to seek it in every moment I live and breathe.

So, no. I no longer need rituals to fuel a connection to something bigger. Just taking a moment to consider where I am–where I really, truly am–in the grandest scheme of things is enough to shatter my relatively tiny, daily perception and pull me into the ever-spiraling dance of the cosmos in all its parts.