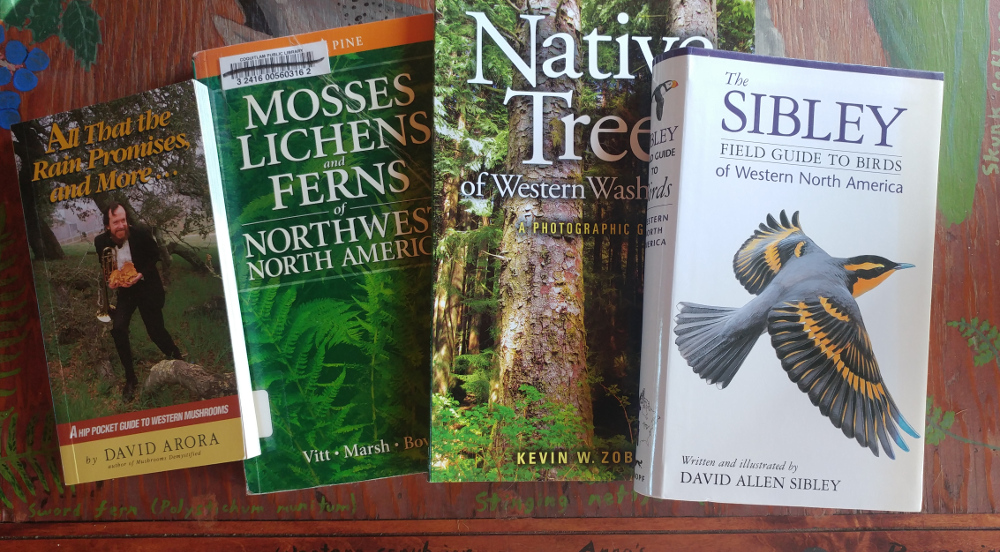

I was talking to someone on Facebook today about how I’m a field guide nerd. I have an ever-growing collection of identification books on the fauna, flora and fungi of the Pacific Northwest, as well as its complicated geology, climate, and other natural features. I even collect vintage ones just for the fun of it. I’m also an avid iNaturalist user and spend a decent portion of my outdoor time taking photos of beings I meet along the way. And I love the challenge of trying to identify some critter or plant that I have never encountered before, just to put a name and a niche to it.

Now, I’ve spent the past couple of decades watching experienced pagans talk about how important history books are for pagans wishing to deepen their practice. They’re right, of course, at least if your path is in any way linked to historical cultures. But think of how many pagans invoke the elements without understanding anything about the earth, air, fire and water in their bioregion, or who call on deities of storm and forest and fertility with little comprehension of those natural forces. We can name entire pantheons of deities and list off magical correspondences for hours, and yet so many of us can’t identify more than a few native plant or bird species. I’ve already asked why we can’t be as nerdy about nature as we are about history in a both/and rather than either/or manner. So consider this a continuation of that query.

Using Field Guides

First, what is a field guide? Simply put, it’s a book or website that lists a certain group of living beings found in an area. Bird guides are by far the most popular as birders are also generally pretty avid book fans, and when you’re trying to fill your Life List with positively identified new species it’s important to be very sure you know what you’re looking at through your binoculars. But field guides to flowers and other plants, mushrooms, wild mammals, and other beings abound. Some of these cover entire continents; others focus on a single state or region. The best have clear, full-color photos or high quality illustrations showing the field marks–distinguishing characteristics–of each species, along with pertinent info on behavior, habitat, and more.

The best way I’ve found to use one isn’t to cart it around with me all the time, but instead to take note of various beings I find in my day to day life. If I can get a picture, great! But sometimes that’s not possible, and so I need to either sketch or write down as many of the field marks I noticed as possible. For example, the first time I saw a varied thrush I noticed that it was a bird very much like a robin except it was yellow and black. When I got home I grabbed one of my Oregon bird guides and flipped through until I found a bird like the one I saw. The size, location and habits all matched up with what I observed, so it was a pretty safe bet that this was indeed a varied thrush.

I also read through my field guides, because there are many beings I have yet to see in the wild. There are several species which I had previously only seen in books and photos, and which I instantly recognized in person the first time because I was already aware of how they looked. Plus it’s fun to imagine what sorts of wildlife, plants and mushrooms I might find if I decide to go exploring somewhere new!

I’ve kept a journal of my nature sightings for several years, and I also have a pretty extensive collection on iNaturalist. Every time I find a new animal, plant or other being, I make note of it in the journal with what I saw, when and where. Then as I further research the ways in which my ecosystem is put together I can place this particular being into its niche and know how it’s a part of the greater whole. The varied thrush, for example, is food for hawks and other predators. As an insectivore it helps to keep insect populations in check. And like all birds its droppings are important fertilizer for plants and fungi, and because it eats berries it helps to distribute the seeds to new locations. I can appreciate the need to preserve forest habitats in particular since the numbers of this species have been declining due to habitat loss. And so now I think of those things whenever I see a varied thrush, rather than just saying “I see a bird. I wonder what it means?”

How Is This Useful to Pagans?

If you’re going to draw on nature in your path in any way, it’s a good idea to have at least a basic understanding of what it is you’re incorporating. Any introductory book on paganism will extol the virtues of getting to know the differences between various deities and spirits and the like so that you aren’t calling on Artemis in a men’s ritual or asking Dionysus to help with a safe ocean passage. In the same way, it’s important to be able to identify at least some of your non-human neighbors if you’re going to be asking them to join your rituals.

And I don’t mean just going with anthropocentric information. If I am going to learn about fly agaric (Amanita muscaria) I’m not just going to look at pictures of Smurf houses or try and pretend I’m a Siberian shaman by ingesting some of this hallucinogen. Instead I’m going to find out this fungi’s natural range, what sort of substrate its mycelium prefers, what sorts of trees it forms mycorrhizal relationships with, and whether there’s any animal that can safely eat it. All these tell me more about how it fits into the ecosystem I am also a part of, and gives me a greater appreciation for it as something other than “one of those mushrooms that can get you high.”

The more you get to know your community, human and otherwise, the more you come to value it. Just as knowing the names of your neighbors and store employees conveys a deeper sense of connectedness, so knowing the names of the animals, plants and other beings around you makes you more appreciative of them. And as you grow your awareness of how your human community works together in a web of inter-reliance, so your understanding of the complexity of your overall ecosystem shows you just how precious and important it is. And that, to me, is the center of truly nature-based paganism. Not how many Samhain decorations are on your altar or how many crystals you own, but how aware you are of just how entwined you are with everything around you and how much responsibility you have to it. If all you do is take, take, take and never give back, even in the simple act of knowing something’s name, then you are a parasite rather than a partner.

Field guides are a great way to begin this healthy and balanced relationship. Like a list of deities in a pantheon, they introduce you to who’s who. You don’t have to memorize every species in every book or website; just knowing which field guide to start with when researching a species is a great first step. And how much you explore is up to you. You may be content just knowing the data in the field guide entry for a given species so that you can name it the next time you see it. Or you may wish to get to know it better, along with the various other beings that it is inter-reliant with, so that you can place a few more pieces into the puzzle of your ecosystem and have a greater part of the whole picture.

How Do I Find Field Guides?

The easiest way I’ve found is to go online and search for “Oregon field guides” (you can substitute your state, region or country for Oregon.) Or go to Amazon and search for “field guides” and see what pops up, though I recommend actually buying your books from local independent bookstores. If you want to narrow it down, search for things like “Oregon plant field guides” or “books on birds of the Pacific Northwest.” If you’re more hands-on, go to your local bookstore and peruse their nature section. I’ve gotten almost all of my field guides from the gift shops at state and national parks and wildlife refuges as I like supporting them financially.

The same goes for websites. Let’s say I saw a salamander but didn’t know what it was. Searching for “Oregon salamanders” brings up several pages that showcase all the species of salamander found in this state. Some of these sites, like the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife’s wildlife viewing site, also include information on other sorts of animals, making them valuable for broader research. Here are a few more links to get you started (please notice some of these are US-based, though there are some non-US links as well):

Encyclopedia of Life’s list of online identification guides

Whatbird – the Search page allows you to narrow birds down by attributes like location, color, shape, etc.

Identify That Plant’s list of plant ID websites

MycoKey – the free online version only allows ID of some types of fungus. I haven’t been able to find a single good online reference for all fungi.

10+ Naturalist Resources for Identifying Wildlife – a few broken links but still a solid list

Does this post resonate with your idea of paganism? Then I bet you’ll enjoy my books! The titles from Llewellyn are particularly informed by my interest in natural history and include more details on how to connect more deeply with the nature around you. Check them out at https://thegreenwolf.com/books/