Last week, a couple of things of note popped up on my social media radar. One was this excellent article by Miranda Campbell, Culture Isn’t Free, talking about how expecting artists and creatives to work for “exposure” leaves the creation of culture largely in the hands of those who hold the money. The other was yet another “paganism on a budget” Tumblr post collecting links to sites where you can download free, pirated pagan ebooks, still under copyright rather than public domain. That post had over 2,000 likes/reblogs, if I recall correctly, and likely has more now.

The first one I read and appreciated, then shared on Facebook. The second I forwarded to the publishers whose books were listed so they could file DMCA takedown notices with site hosts. The difference? Ms. Campbell had an agreement with Jacobin as to how her writing would be distributed and how she would be compensated (if at all; I’m not privy to their arrangements). Such websites want links to their content to go viral, and I thought it was worth sharing. But with the website that was linked on the Tumblr post, there was a violation of the terms that the authors of the books had originally agreed to. Part of the publisher’s job is to maintain the terms of the contract, to include fighting privacy; they have more resources, on average, than a single author does.

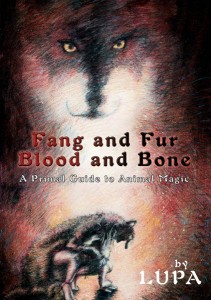

The publisher-author relationship isn’t perfect. Ten percent royalties is still only a couple of bucks per book, and most authors don’t make a living on their writing. But the author still has the choice to negotiate a contract, and then sign or not sign it. It’s their decision to make their work available through a particular, if often imperfect, avenue that will at least get them some compensation for their effort. And in an economy where creatives are increasingly asked (or told) to work free of charge, some compensation (protected by contract) is better than none.

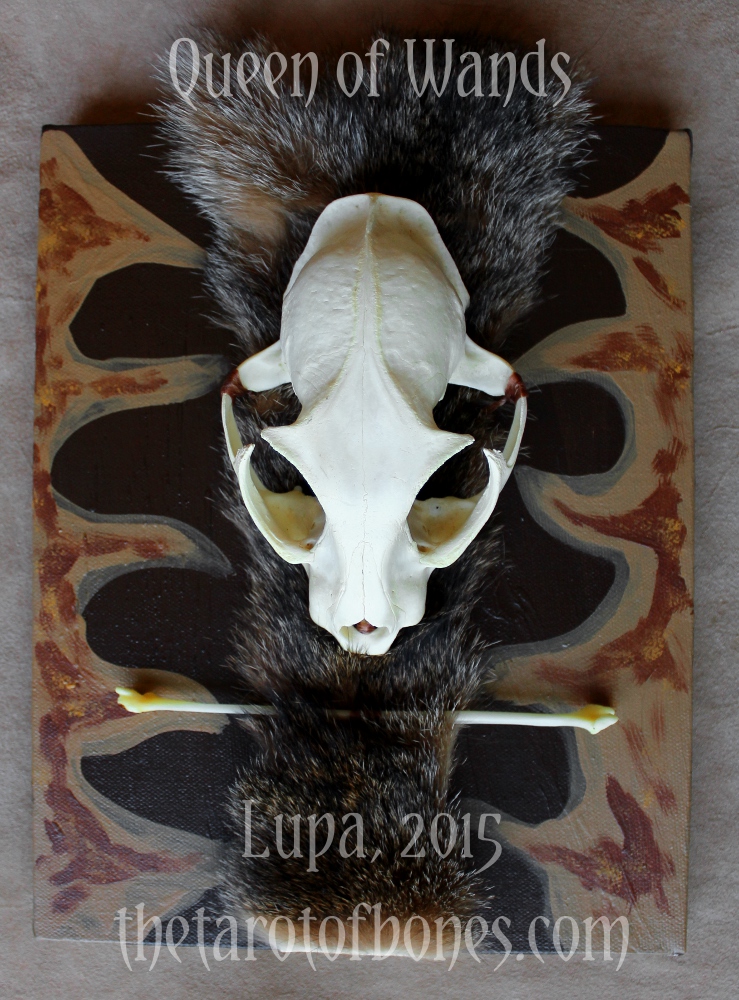

And to be fair, the publisher does a lot of work. When I sign a contract with a publisher for one of my books, I’m getting free editing, proofreading, layout and distribution, along with a certain amount of promotion. With my artwork, on the other hand, I’m carrying almost all of the burden, from materials acquisition and design creation to actually making the art to selling it in person and online. Either way, each sale of a book or piece of artwork funds far more than just the item itself.

So we have to put a price on that time, effort and investment of resources. One of the biggest challenges I’ve seen artists (especially newer ones) face is how to price their art. A price is not merely a number. It’s a statement of value. What is this item worth, not only for its content, but the human resources that were poured into it from start to finish? What costs were incurred in its gestation and birth? And, more importantly, what is the value of the human life that was invested in it, time that needs to be measured in dollars rather than breaths? It’s a difficult thing to determine, and even after almost twenty years I still struggle with pricing my work. (My publishers make the job easier by setting the price on my books themselves, gods bless them.)

So we have to put a price on that time, effort and investment of resources. One of the biggest challenges I’ve seen artists (especially newer ones) face is how to price their art. A price is not merely a number. It’s a statement of value. What is this item worth, not only for its content, but the human resources that were poured into it from start to finish? What costs were incurred in its gestation and birth? And, more importantly, what is the value of the human life that was invested in it, time that needs to be measured in dollars rather than breaths? It’s a difficult thing to determine, and even after almost twenty years I still struggle with pricing my work. (My publishers make the job easier by setting the price on my books themselves, gods bless them.)

Eventually a price is determined, and placed out for the public to view. That price says “This is the amount of money that I will accept for this product of my work.” It’s the same as a contractor saying “I want this much per hour to fix your sink” or a pizza place stating “Here’s how much a large cheese deep dish pie will cost you”. It is an invitation to an economic contract that is signed when the money is passed over. A simple agreement, sure–you give me that thing, I give you this thing, we consider it a fair trade, we go on with our lives.

There are always people who try to weasel their way out of that agreement. Some of them steal outright. I’ve lost track of how much of my artwork has been shoplifted from my booth at events I’ve vended at over the years. Only once has anything been brought back, by a tearful preteen girl flanked by her angry mother. The rest is spirited away by malcontents and children who don’t seem to understand the damage they do by their actions. But books get stolen, too, and far more often in the digital age. Every person who downloads a pirated .pdf of a copyrighted book is a thief*. It’s not the same as a secondhand paperback bought new and then sold used later on; that’s a single copy that was fairly compensated for, and it will never multiply into more copies (at least not without the help of Xerox or a scanner.) But a .pdf multiplies by its very nature, and within seconds. Whereas a paperback can pass from person to person in a circle of friends, and perhaps circulate among a dozen people in a month if they’re all fast readers, a .pdf can go to thousands of people in a day, and they get to keep their copies no matter who else they pass the book on to. Either way–art or books–the creator is the person who loses out in piracy.

But that’s not the only way the “I offer you this in exchange for this” agreement can be damaged. Allow me to present to you: the haggler. This is that person at events (or via email) who, dissatisfied with the numbers on the price tag, and weaned on Wal-Mart’s “Low Price Guarantee”, decides that they should have the privilege of paying less for a creation than its creator has valued it at. And so they approach said creator and, holding up a piece of art like a yard sale discard, ask “Will you take five bucks for this?”

To be honest, I consider it somewhat offensive when someone asks if I’ll accept a lower price on something I’ve created. I know it’s likely not meant as an insult; the person asking just wants to save a little money. Who doesn’t want that? In an economy where big box stores lure people in with ever-bigger sales and price slashes supported by government subsidies and slave labor, consumers have been trained to get bargains and they never think of who actually pays the costs for their savings**. It smarts more personally, though, when they try to do it to an individual artist. It’s not just that they’ve asked the creator to take less money; it’s that they treat the creation like it has no personality, no love poured into it. It’s just a thing to them.

Haggling, shoplifting, piracy–all these are symptomatic of a bigger cultural problem: the devaluation of art. I have yet to meet an artist who hasn’t at one point or another heard some variation on the following:

“It’s just art, you have fun making art, so it’s not actually work.”

“Will you make me this thing for free, or the cost of materials?”

“It’s exposure–it’ll get you more customers, really!”

“Oh, my aunt/kid/friend made something like that!”

“I bet I could make that!”

“It’s easier to be an artist than a scientist/real estate agent/hotel manager so you shouldn’t expect to get paid like one.”

Sure, lots of people make art as a hobby, and even for those of us who do it for a living it can still be fun. But as I wrote last year, Art is Work. If what you do for a living is fun, then you’re doing something right. But that doesn’t take away the amount of effort you put into it. And only you can truly know the value of that work, and decide whether the compensation you’re getting is worth it or not.

Sure, lots of people make art as a hobby, and even for those of us who do it for a living it can still be fun. But as I wrote last year, Art is Work. If what you do for a living is fun, then you’re doing something right. But that doesn’t take away the amount of effort you put into it. And only you can truly know the value of that work, and decide whether the compensation you’re getting is worth it or not.

When someone shoplifts your art, or pirates your book, or tries to haggle you down from your prices, they are saying that they don’t think your work has as much value as you say it does. And in that moment they are insulting you and your work. Any compliments they have given “Oh, I love this piece, it’s so pretty” is tainted by their unspoken follow-up “….but I don’t think it’s worth all that much.” It’s up to you as to how you want to deal with them, but don’t for an instant think that your work isn’t worth what you value it at, no matter the words of thieves and hagglers.

We are artists and writers and creatives. Our work and our time have value, and we deserve to be compensated for our effort, and to be able to decide how our work will be distributed and offered to the public. Nothing less is acceptable.